By Mike Koetting February 17, 2026

While the mid-term elections are ten months off, and ten months is a political eternity, polling suggests it is very likely Democrats will gain a majority in the House and might even eke out a tiny Senate margin. Inshallah.

One hopes this would allow the Democrats to serve as a somewhat greater brake on Donald Trump’s worst impulses. The degree to which that will happen is unclear since so much of what he does is, to be generous, extra-legal. Thus, the ability to slow him will play out in real time when we get there.

Still, having a plan might be good. Here are a broad set of strategies that Democrats might use as a framework for the following two years—if they are willing and able to do so. I think the difficulty of following these strategies will be less a function of Trumplican opposition and more a function of the party’s internal workings, which, by the way, are not unique to Dems but are inherent in the way we allowed our pollical and cultural environments to evolve.

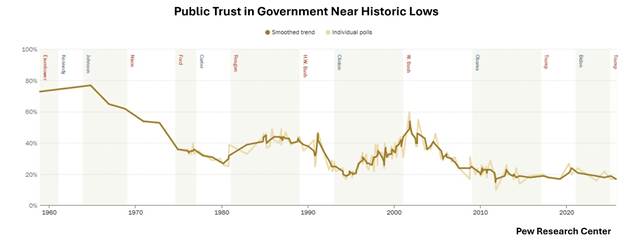

Before getting to my general strategies, I would suggest one uber-strategy: think long term! Not only 2028, although that is essential, but even beyond that. America is facing serious problems. The majority of citizens do not believe the country’s overall values are holding, its government is working for them, or that either of the political parties represents their interests. In such an environment it is possible to cobble together various short-term victories—somebody has to win an election—without achieving any trajectory-changing goals. Real change will require setting significant goals, conveying the limitations of the moment without throwing cold water on goals.

In that context, I think the general approach to the next two years for Democrats should be to focus on staying positive and minimizing recriminations, outline the “affordability” issue in a realistic way that points the direction for what could happen after 2028, and resolve the immigration issue to a point that it no longer overwhelms more serious issues. Each is explored below. Settling for these may seem like too much compromise, but the absolute core of democracy is to make compromises among imperfect options.

Stay Positive

While a more Democratic Congress seems likely, no polling suggests Democrats can achieve a large enough margin in the Senate to actually make far-reaching changes, let alone pass any impeachment or otherwise provoke a fundamental Constitutional challenge. Which is probably okay because a large portion of the electorate isn’t even interested.

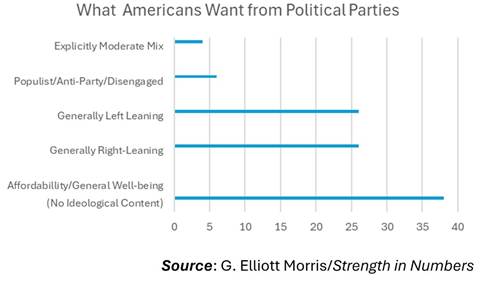

Most voters do not place the same weight on certain pollical values that I, and most of the readers of this blog, place on them. As hard as it may be for you and me to imagine, many voters see all of this as squabbling between two pollical parties—that they don’t care about—while their fundamental problems go unaddressed. (Somewhere between 20% and 25% of voters—that is people who say they actually voted—do not know which party controls Congress.) They can be worried or relieved about something that impacts them directly, but they don’t put it into a broader framework. G. Morris Elliott has done some interesting work where, instead of asking people where they stood on issues, he asked them what they wanted from their ideal political party. Any attempt to sort the infinite flavors of human imagination into groups is of necessity a form of nominalism and, accordingly, bound to be inaccurate. Still, the broad groups that emerge in his analysis make intuitive sense. (The detail is pretty interesting, as is a confirmation/explication by Steve Genco.)

This suggests Democrats would be better off by focusing on things that are directly related to people’s well-being. People generally value democracy, but they aren’t interested in hearing others talk about it.

Since it will presumably be very difficult to pass transformational legislation, Democrats should make sure that whatever they lose is a “productive loss”—that is, that illustrates the difference between the two parties not in terms of us versus Donald Trump, but in terms of “this is what we will do for you if the Republicans weren’t opposed.”

Establish a Pathway to Economic Stability

This is mostly at the core of what people are looking for—and the most difficult to change. There are neither quick nor simple solutions to the economic problems facing America. They are a product of 50 years of economic mismanagement—more by the Republicans but with large amounts of Democratic complicity. Unwinding them will be a Herculean task and will get nowhere in two years with only a small majority to work with. It will take a much bigger majority to rework the economy which, for the past 50 years, has been running on the idea that open lanes for the highest return on capital are more important than maintaining social solidarity.

So what would a relatively slim Democratic majority do? The first thing I think they need do is acknowledge what has happened, including their role in it. They then need to make it as clear as possible they understand the stakes and are prepared to do major, even radical, battle if the voters create a Democratic administration in 2028. Achieving much of a consensus around such a position, unless it is watered down to pablum, would be an accomplishment. Democrats, no less than Republicans, are entangled with big money. Such an exercise might also go a long way to solidifying the 2028 Presidential field.

That said, I don’t think it is desirable to approach 2028 without some real “affordability” result on the table. Promises of longer-run actions are good. Study commissions, hearings, town-hall meetings, white papers all focused on developing what could be done with a healthy Democratic majority are great. But voters need to see something tangible.

I think the best, immediate thing Democrats could do is take on health care (and synonymously) insurance costs. A complete fix here falls into the “long-time, really big” category. But a possible short-term step is to restore funding for Medicaid and ACA programs. The underlying fact is that the reductions in ACA subsidies not only punish people who must forego that insurance, but they wind up increasing costs for anyone who uses healthcare services since the remaining healthcare users now have to also cover some of the costs formerly covered by those programs. This is difficult to message—particularly given the strong anti-message that these are another give to poor people (or insurance companies). But I think enough people in power understand the underlying mechanics and, combined with the innate inhumanity of withholding health care from people, it would be possible to make real progress on this in two years.

To repeat what I said before: what needs to be done in healthcare is much more fundamental and there is no harm in stating that. But it seems prudent to differentiate between what we can do now and what will take longer

It is also likely that some other issues will present themselves where Democrats can strike a blow for affordability—or, if they are blocked, pin it on the Republicans. But somewhere in all this, if the Democratic Party is going to survive, it is going to have reorient itself to drastically restructuring the American economy with a clear goal of reigning in corporate power, reducing the influence of the super-rich, and making the economic life of average people more secure. And I can’t see how that can happen without larger legislative majorities than are likely after this November.

Get Immigration Off Infinite Boil

I think this is one big thing that can be done now.

Immigration is a substantial concern for a large portion of the country. Both parties have recognized this. The Democrats, seeing that, have offered major compromises. While painful—particularly to some elements of their core constituency—these were reasonable reflections of what the country’s majority wanted. Each time, Republicans, more interested in preserving the ability to use this as an electoral club than to represent the people, have tanked these compromises.

The current Trump fiasco around immigration has made concrete to a great many Americans the problems of enforcing what they thought they wanted. This, in turn, has deprived the Republicans of the platitudes they have previously relied on and created an environment for a compromise that would allow the country to mostly move on from this issue, assuming the Democrats don’t overplay their hand. The current antipathy to ICE-overreach does not translate into a broad retrenchment on the overall issue.

A working compromise would include seriously tightened border security, a careful rethink of asylum rules, deportation of people with serious criminal records, and a path to citizenship for many people who have been here for some length of time, certainly including the dreamers. It would also probably include deportation of some immigrants who are here illegally for shorter periods of time, even if they are not guilty of crimes.

One might object this is using some of the immigrant population as pawns. True. But less so than the current situation and, presumably, in a more stable situation. There are simply no solutions here that fulfill a Platonic ideal of fairness. Adopting a do-able compromise would improve the lives of many and would allow the voting public to turn to other issues.

In Short

It is unlikely that November will dramatically change the political landscape. Better for Democrats to use the next two years focusing on the longer term than spend time on projects with low likelihood of return and little political support beyond their base.