By Mike Koetting January 6, 2026

The question of what one generation owes to the next is a complicated one, but I am struggling to find any register on which American society is doing a good job of giving young people what they need to have good and fulfilling lives.

This and subsequent posts will look at three important areas where as a society we seem to be doing a particularly poor job facilitating the next generation’s route to good lives. Today’s post will focus on young people in the economy. The next two will consider how we are treating post-secondary education, and, finally but more broadly, what view of the future we are giving to the people who will live it.

Widespread Problems Have Disparate Impacts

Many—perhaps most—of the problems in our economy apply to many age groups, not just young people. But, as I will try to show, the damage to young people is particular, mostly because of the way it shapes their outlooks and their life-long trajectories.

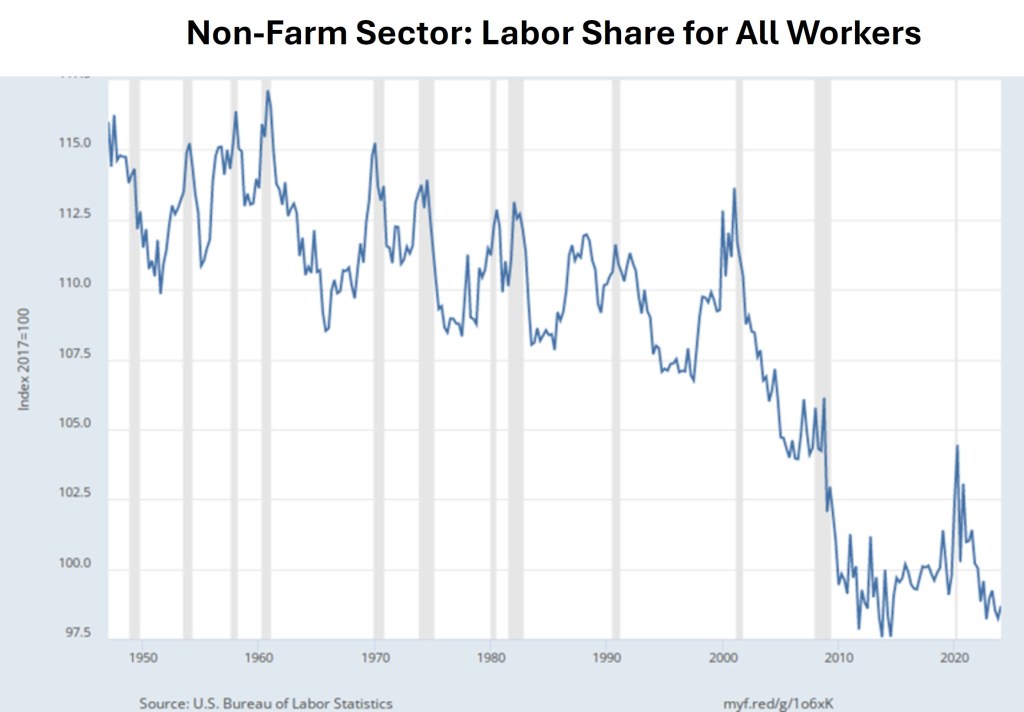

The core problem of the American economy is that the benefits of the economy are going disproportionately to capital rather than labor. We’ve all seen the graphs.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

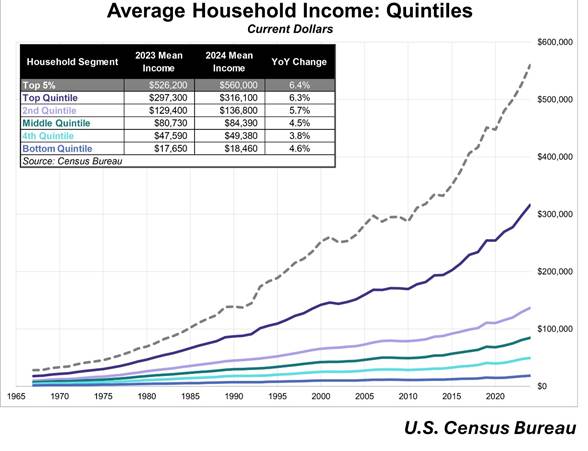

Which, of course, has led to a serious divergence in income growth among various cohorts of the economy, with after-inflation growth of the top tiers seriously outpacing the rest of society.

Again, while this impacts everyone in the bottom 80% of the income distribution, the impacts on young are magnified. They have no resources on which to fall back. They are seeking for the first time many of the things all adults want to have–their own car, have their own place, be able to imagine starting a family.

One consequence of these immediate difficulties is that a great number of young people can’t understand how they are going to make their way in life. This is a major change in the social framework of our society. From the end of World War II until, somewhat arbitrarily, the 2008 recession, there seemed to be multiple life paths. Not that they were equal and their real-life availability varied across the population. And cracks started showing well before 2008. Still, most people coming of age over that period could readily imagine a track to a good life—professional, white collar, gray collar, or blue collar. All of these tracks, in varying degrees, promised employment at a wage that afforded a house, a car, and a vacation. It was simply assumed that these jobs would offer health insurance and pension. In that context, marriage and kids made sense. The gradual accretion of women into the labor force helped ice the economic cake, even if it created other issues

By contrast, most of today’s young people are deeply skeptical these pathways will be available to them. For many, they are already facing serious headwinds. In a poll of young people by the Harvard Institute of Politics 43% of people in their sample reported struggling or getting by with limited financial security— and this strain is especially pronounced among Black and Hispanic young people and those without a college degree. In another study of young people, nearly 40 percent of survey participants said they were taking on additional jobs to make ends meet.

Bad Job Market

One of the biggest problems for young people is that the job market is inhospitable. Even those who have graduated from college can find the sledding difficult.

The three-month moving average unemployment rate for recent U.S. grads sits around 5.3% versus 4.2% for the overall workforce; on some measures for degree-holders it pushes ~6–7%. This is being driven by a number of factors. In some cases, it is in fact AI, or, more likely, the expectation of AI. It also reflects the economy of not hiring people who will take a while to ramp up their skills. Both of these have become problematic for today’s cohort because it is looking increasingly likely that during the economic “bounce back” from the pandemic many companies over hired on the assumption their growth would continue at that pace. It hasn’t. With insufficient demand, companies would have to lay off workers to make new hires. They don’t want to. And the problem is amplified because consumer confidence is in the toilet and people are unwilling to leave the jobs they already have. When there are fewer voluntary movers, the number of job openings decreases. All of this generates a longer-term problem because when young people don’t get starting jobs, they are blocked from the opportunity of on-the-job learning and run the risk of permanently lower income and skill levels.

The problems for those who would otherwise head into blue collar jobs are different in particulars, but similar in outcome. On balance, manufacturing jobs in the US have declined as a part of the workforce. This has been going on for years but has recently accelerated dramatically, falling by almost 25% since 2020. This is driven by both automation and trade policies. When total jobs in a field disappear, there are inevitably fewer job openings, which of course is disproportionately felt by young people, setting in motion a chain of problems that stretch over a lifetime.

Student Debt

I have heard many adults dismiss the issue of student debt as some version of “entitled young people”. I am not sure they understand the magnitude of the issue. One in four adults under the age of 40 have student loan debt. This totals to about $1.8 trillion held by 42 million different people, most of them between the ages of 20 and 40. In 2025, the average amount of the loan debt is $50,000, And while there are some people in this mix for whom the student loan was the ticket to a very well-off life style, there are many more for whom this was a marginal investment, or, worse yet, yielded no tangible economic advantage.

To be sure, what’s going on with student debt is intractably related to the cost of college and, further, its role in our society. I will return to these in the next post, but here I am simply pointing out that student debt is a major economic fact in the lives of young people. There is evidence that by itself it reduces home ownership and negatively impacts family formation. It can materially impair credit scores, which leads to higher rates for everything from credit cards to mortgages.

It is hard to put these policies into a global perspective because so many aspects of American post-secondary education are unique. But other countries have chosen different approaches that result in little to none of the anxiety that we have created in America. For all the heat the discussion has attracted, neither party has put forth an agenda remotely commensurate with the problem. Impact of recent changes as part of the Trump administration is still being sorted out—and may include some very modestly useful reforms. But the decision to renew garnishing salaries for delinquent student loans will certainly cause some real hardships.

Housing

The increase in housing costs is well discussed as a problem afflicting all portions of the population. Inflation-adjusted housing costs, rent and purchase, have increased almost 25% more than median wages in the last five years. The result is that the entire bottom range of the income distribution is facing increasing difficulties in affording housing.

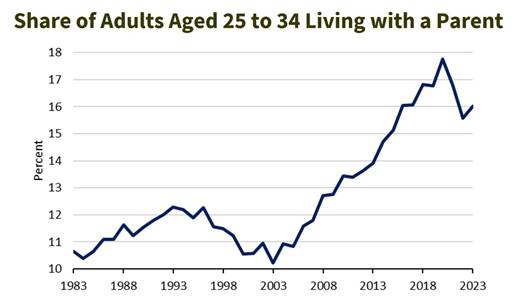

But, again, the impact on young people is particularly stark. Median age of first time home ownership, for instance, reached 40 this year, an all-time high according to the National Association of Realtors. The following chart is a poster for the problem.

In Short

Darren Walker, President of the Ford Foundation, said “Hope is the oxygen of democracy.” But it’s not at all clear that the current economic situation is generating hope in young people. Rather, it is raising concerns as to whether they will find jobs that pay enough for a comfortable life, be able to own their own home, be confident they will have health insurance, be able to afford children or retire at a reasonable age. And while all young people have some degree of apprehension, it would be inexcusable to overlook the greater pessimism about having a good life among those who start out with few advantages. It is no wonder so many feel the game is rigged.

Rather than generating hope, then, I am worried the current situation is generating fear in young people. That is a very bad thing. As Yoda says: “Fear is the path to the dark side. Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to hate.”

And hate, as we have seen, is a threat to democracy.