By Mike Koetting October 22,2024

Well…I am tired of the election. I don’t think I have anything more to say about it until it actually happens. Anyone reading this knows what I think. None of us have a clue how it’s going to end. Neither do all the pundits, who at least get paid for making up the same stuff that I would. We’ll just have to see.

On the other hand, it’s hard to talk about anything else. It’s like trying to have a conversation on the side of the runway while three dozen Boeing 737s are taking off, with of course, the possibility that one will crash.

Nevertheless, I am going to talk about something else—the longshoremen’s strike that streaked across the American consciousness and is already forgotten because it turned into a non-event. Before I get into the main part of that discussion, I can’t keep myself from making one election related point: the longshoremen got a huge raise because they had a strong union and because the White House weighed in as a real, working ally. In office, Trump did everything he could to undercut unions. And, while he was full of bluster about what he would do for workers, he never delivered squat, particularly in comparison to what Biden and the Democrats have delivered. Any argument by union members for backing Trump for economic reasons are wildly suspect. I have argued elsewhere that there are real economic issues in the society and that the current economic successes don’t scratch all the valid itches. But still, if you’re a union guy and you say you support Trump for economic reasons, you’re either lying or are deluded about what can possibly be accomplished by policy. (A recent book by Lainey Newman and Theda Skocpol, who was one of my mentors in graduate school, argues that what has so badly eroded Democratic support from labor is that the weakening and dispersion of American manufacturing has not only depleted union membership but more fundamentally destroyed the sense of working-class culture that was important in creating union solidarity. This surely contributes to the confusion as to who is really on their side.)

But on to the main feature, the longshoremen’s strike. Beneath the obvious labor-v-capital struggle, there are several thorny issues that are likely to become part and parcel of labor discussions moving forward.

Start with the money. The 47,000 members of the International Longshoremen Association (ILA), which represents the longshoremen in the Eastern half of the country, went on strike on October 1. They were seeking a 77% increase in wages over the next six years. It was their first strike since 1977, although they have benefitted from the more aggressive tactics of their West Coast brethren, represented by the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, who have struck several times in the last 45 years.

By any standard, the increase sought by the ILA would have been large. On the other hand, since the just-expired contract came into effect in 2018, the shipping companies have made “record profits totaling hundreds of billions of dollars,” according to a report in the Wall Street Journal. Some of those hundreds of billions came during the pandemic, when shipping companies, responding to the increased sales in goods, raised their prices to unprecedented levels.

Current wages for these longshoremen are some of the highest for union worker anywhere in the country, with average salaries more than $100,000. (West Coast longshoremen make more, often over $200,000 annually.) This is largely a result of a deal made in the 70’s, when the longshoremen agreed to accept containerization of shipping for increasing wages that reflected the resulting increase in productivity. Containerization dramatically decreased the cost of global shipping and is an indispensable underpinning of the current global trade situation. This shift, however, greatly reduced the demand for longshoremen, in some ports by more than 90%.

In any event, after two days, the ILA strike was suspended until early 2025. The pause came after the shippers agreed to a 61% increase in wages over the next six years.

Still To Be Addressed

There is another issue lurking in the discussion. The shippers are looking for a future with a second major reduction in the number of longshoremen through further automation. A white paper from Michigan State says future automation could reduce the number of longshoremen by as much as 50 percent. One of the precipitating events in the lead-up to the current strike was an argument about a specific automated gate that allowed loads to be analyzed without involvement of longshoremen, who had traditionally done this job.

At least for the time being, major reductions in workforce are unlikely. Those ports that have invested more in automation have been well studied and they show that labor reductions are substantially below estimates. In the intermediate future, there are much larger efficiency gains to be achieved by greater coordination around how cargo comes into ports and leaves after being unloaded. But, as most analysts have noted, the technology will get better.

So, what should the ILA be demanding when discussions with the shippers begin again in January? At present, the ILA is seeking a ban on certain automated equipment that eliminates the need for longshoremen on those tasks. I doubt in the end they will risk the wage gains that have been promised for this provision. I am confident some face-saving compromise will be reached. No matter what anyone says, the main issue is always about the short-run money. The future is too far away.

However this specific issue gets resolved, it will only kick the can down the road. The technology will continue improving and soon or later, ports will be able to load and unload ships with fewer longshoremen. This raises the question that we are facing in many sectors. How do we want to respond to the possibilities of greater automation? There are obvious benefits to humans. Ports with greater automation show improved safety for longshoremen. And it doesn’t make sense to have people in “make work” jobs. But we don’t have a template for structuring a society where work is not a central element of identity, not to mention economic status. The consequences in areas that have de-industrialized have not been encouraging.

The longshoremen have the protection of a relatively strong union. Harry Bridges, legendary leader of the West Coast Union, once said: “There may come a day when the entire port of San Francisco is operated by one guy pushing a button, but he’ll be a union member and the highest paid SOB in the world.” Good for him. (Or her, since one of the benefits of automation is that button-pushing is not gender related.) But what happens to the rest of the union? Or the many people whose unions don’t have that kind of leverage or who don’t have a union at all?

I suspect automation, AI and other technological changes will actually eliminate jobs more slowly than predicted. The experience of ports in achieving automation will be typical: technology will have some dazzling applications that on paper should eliminate a lot of jobs. But when put into practice, the loss will be much more gradual. Add that to the broad experiences of the last several hundred years that society has been able to find work for those who lost their job through innovative upheavals and, in the process, create a society where there is much greater material comfort. So maybe the longshoremen are right to worry, but to focus on using their leverage for their immediate benefit.

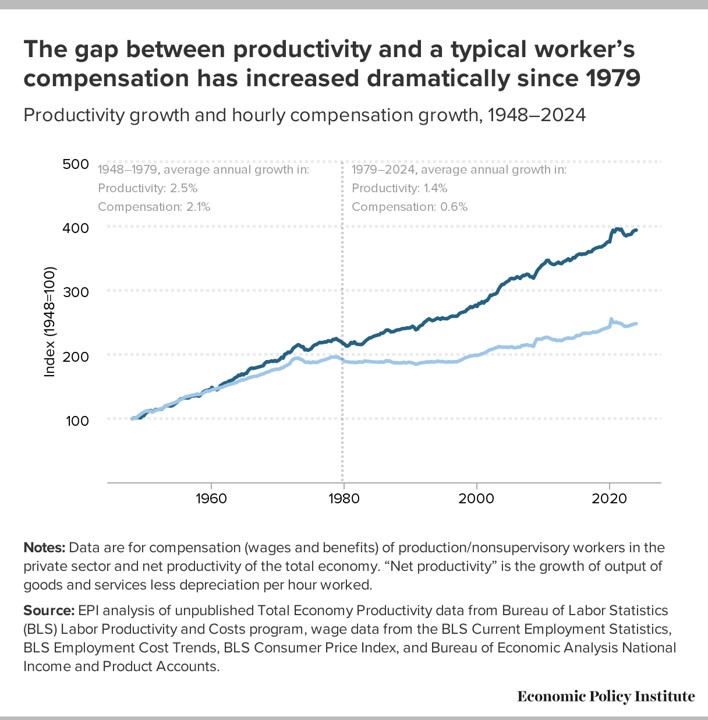

This is understandable. Labor has been getting shafted in the division of the returns from increasing productivity wrought by automation. From the end of the Second World War until the rise of neo-liberalism in the late 70’s, wages and productivity increased at roughly comparable levels. Since then, more of the benefits from increases in productivity have gone to capital. Not coincidentally, this was when unions lost power and governments—mostly Republican, but some Democratic—soft-pedaled their responsibility as a force for equality, or, in Reagan’s case, used his bully pulpit to renounce it. Had workers’ wages continued to rise in tandem with productivity, we would have much, much smaller income differentials in our society than we do.

The longshoremen have been able to make their wages follow the growth in productivity in their industry. But they did so by sacrificing the number of people in their ranks. Writ large in society, it’s not clear this is a sustainable model. We need to ask who is going to think about how that is going to play out. I am very worried that by default this will be left to the actions of capital. For better and worse, capital’s job is innovation, not thinking about the consequences.