By Mike Koetting June 18, 2024

Over the last several years, I have realized that “the rule of law” is only secondarily related to laws. It is a lot more inchoate and contingent than anything as concrete as a law. At root, it is nothing more—and nothing less—than a vague agreement among a populace that they are willing to share a common project of governing under some loosely agreed upon rules, even if—indeed, because—there are other values they don’t share. Absent that agreement, no laws or no courts can make democracy work.

I suspect at any given time over the last 150 years, there were a discernible number of citizens who viewed some social error so fundamental that this agreement to govern jointly in toleration should be dissolved. But as long as the number willing to carry on was a substantial majority, the agreement sustained and bumbled on to its next crisis.

Consider, for example, Brown v Board of Education. Conservatives are right. This was “judicial activism.” There was no new law that supported this. In fact, it went in the face of a bunch of existing laws, most of which had been upheld by various courts. The Constitution hadn’t changed in this area in 70 years and courts had been okay with it. It wasn’t that a major portion of the population was calling for change. Rather, a small group decided that the fundamental operating agreement needed an adjustment to ensure that everyone got to enjoy the tolerance of the rule of law.

When the decision came down, there were clearly some people who thought it deserved taking the country apart. And a larger group that thought the ruling was clearly wrong and endlessly maneuvered to obstruct it. But the majority of citizens went on with their business. Maybe some thought that, however uncomfortable, it was a time that had come. And surely a lot didn’t think much about it. It took a long time for the import of this court decision to be realized—in many ways we are still not there—but over time most of the population accepted that the continuance of Jim Crow was problematic and, just as importantly, this was an okay way of working things out.

In Bush v Gore, in 2000, the Supreme Court, on a partisan vote, overturned the Florida Supreme Court’s decision to recount certain disputed votes. With no recount, Florida’s electoral votes and the election went to Bush, despite Gore having won the national popular vote by 500,000. There was certainly grumbling and hard feelings, but no one was in the streets threatening civil war.

Where we are today is different. There is a real possibility the existing operating system will come to an end.

How Did We Get Here?

Any political situation is a very messy salad of values, motives and interests. They interact with each other and even in any given person they represent a shifting spectrum of concerns. The current situation has some of the usual characters. There are people who have a fixed self-interest (e.g. lower my taxes) and will consistently vote those values. There are also typically some committed ideologues at either end of the spectrum who have full blown agendas and are just waiting for their champions to score a decisive victory so they can implement their agenda. Most of today’s Christian Nationalists fall in that category. And while their extremism amplifies other tendencies, sometimes in terrifying ways, such groups are a continuing feature of our politics.

But today there is an underlying circumstance and precipitating actors that differentiate from previous years.

Adverse Condition: An Alienated Population

A reasonably-sized slice of the population feels cheated. This is not always rational but neither is it hallucinatory. The country is more clearly separated into winners and losers than at any recent time.

This situation is not measured in high-level trends. At issue is whether individuals feel they are comfortably participating in the “mainstream” and can expect a secure future. A material portion of the country feels they aren’t—and they are not going to. There are disputes among economists as to whether, on average, people are slightly better off than pre-pandemic (wage increases net of inflation) or slightly worse off. But it is beyond dispute that a great many people feel they are worse off and worry that they are about to be priced out of the mainstream, or have already, because of housing costs, food costs, childcare costs, or whatever. The more people hear about AI and environmental issues, the worse the future sounds. All the negative directional signals get magnified and, for most people, direction is crucial in making an evaluation of circumstances.

The depths of this dissatisfaction cannot be sugar-coated. And while the idea that Republicans would actually help seems fanciful, that is beside the point. A lot of people correctly believe they are losing to the rich. Various proposed alternatives—while no doubt sensible—appear to those struggling as not particularly relevant to their lives. Consider the Trump tax cuts. Most of us see them as an outrageous gift to the rich. Which they were. But it is also the case that the actual percentage cuts were greater for lower income citizens. From their point of view, this was cash in their pocket. What happened to those with high incomes is an abstraction; it feeds into their belief they are getting screwed, but they don’t viscerally embrace policy about what could happen. Among other things, they have little confidence it will actually happen. Money in their pocket and lower costs at the pump are concrete. Tangible beats abstraction hands down.

Compounding this economic division are the disorienting demographic and cultural shifts. Both the shifts and the disorientation are real and dramatically complicate the acceptance of a political order when so much else seems in play. Even if someone didn’t really like it, it was easier to accept a mandate to desegregate when your net wages are going up, your benefits are improving, and you feel economically secure. When none of those feel true, you’re less interested in accepting immigrants or gays. That the “thought police” never seem satisfied and consider your beliefs irrelevant is salt in the wound.

Some of the alienated have simply given up on the political system, particularly among the young and Blacks. But a bunch of them are so mad they are open to something drastic.

Precipitating Cause: Craven Political Class

The flame to this tinder is being supplied by Donald Trump and a Republican party willing to subvert the existing rule of law to gain and hold power.

There have always been demagogues and hucksters. And neither political party has been above hinting that the other party is a threat to democracy. But in the past, the leaders of both parties recognized there were limits. In 1974, also a time of cultural upheaval and descension, , when Richard Nixon became mired in scandal, Republican leaders pressured him to step down.

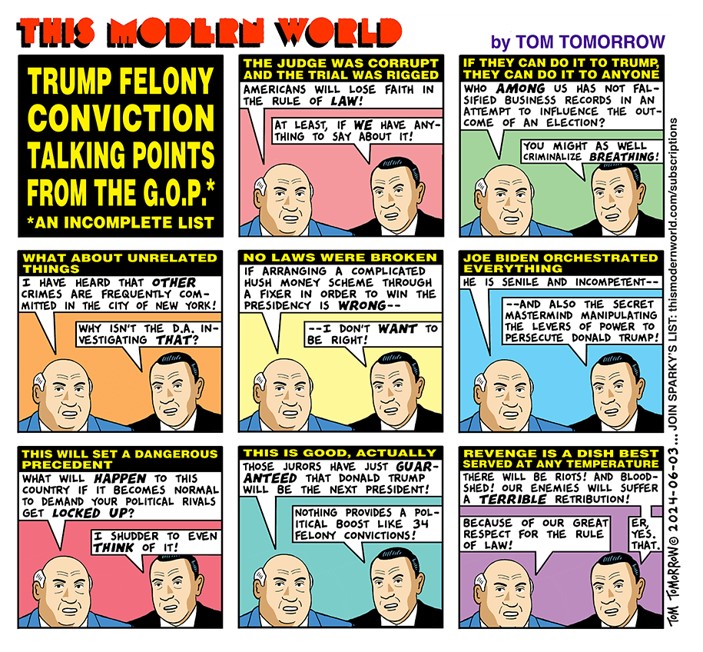

Today’s Republicans have decided anything that works is acceptable. Even if that means catering to—or encouraging—those who value the hope of quick fix over the rule of law. The essential political argument today in America can’t be addressed by arguing through any specific policy or legal issue; Republican policy points vaporize on a moment’s notice. Republicans did not even bother to outline a policy platform in 2020.

This election is about one thing only—does the majority of society support the arrangements we have lived under for at least the last 150 years or is it willing try something radically different. I don’t know what percentage of MAGA voters understand how significant a departure Donald Trump’s ideas are from the historic American operating system. My guess is that some recognize various pieces as radical and are more or less okay with that. But most simply don’t recognize Trump’s agenda for what it is.

On the other hand, the Republican Party leaders understand. And they don’t care. If getting power means letting Trump write the rules from his imagination rather than any recognized process of sharing, deliberation and compromise, so be it.

In other words, one major political party no longer supports the general agreements that have shaped our government. As Mitt Romney admitted: “A very large portion of my party does not believe in the Constitution.” It’s not the specific words of the Constitution that are at issue. It’s the underlying spirit.

Republicans of course cloak their arguments in terms of the Democrats being the ones who have given up on the underlying agreements of our government. Many of their supporters seem to believe that. However, to allege that Democrats are a bigger threat to these agreements is as absurd as suggesting it would be okay for Donald Trump’s supporters to ignore it if he were to shoot someone on Fifth Avenue.

What Happens Now?

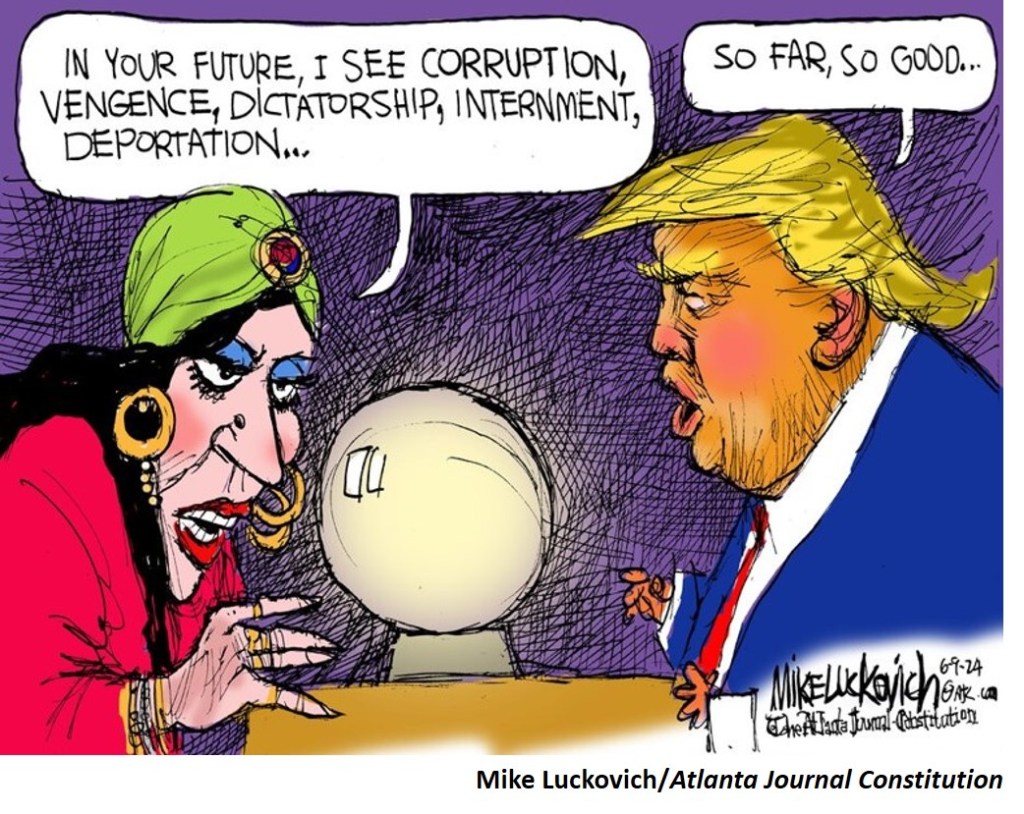

I don’t know, but I don’t see how it’s good. Whether or not the voters understand, if Trump wins, our democracy based on some idea of the equality of humans is on life support. While here is no coherent Trumplican ideology, Donald Trump has made it clear he wants to govern on an agenda of vengeance, grievance, and the insistence on loyalty above all. He, and some of his cronies, are more than willing to cozy up to some of the extremist Christian nationalists.

How much of that agenda the Trumplicans would actually pursue is uncertain. But where it fits with their authoritarian desires, they are on board. Remember, the issue is not policy; it is controlling the rules by which society conducts itself. Once a group of people are in power who have little regard for majority opinion or opinion of any minority that disagrees with them, the rule of law is gone.

One of the Trumplican challenges will be that it is unlikely they can actually fix the concerns of the alienated who would be essential in bringing them to power. There are things that could make our economy fairer. But neither Trump nor the other leaders of the party are inclined to actually do them. Controlling AI or addressing environmental issues would also require steps unlikely for this group. Trump presided over a good economy. But the inequality in the economy got worse, not better. In any event, it’s not clear how much his policies actually had to do with it. And what he seems to be proposing now clearly won’t help. It is disconcerting how much rationality has been given up for catharsis.

If Trump loses, it will be a different sort of ugly. There is a plethora of armed Trump supporters who are threatening violence if he loses. I am not sure how many of them would follow through. More to the point, it’s not obvious to me what structures would be available to channel the openness to chaos into something that might look “revolutionary.” I would rather expect an outbreak of mild-violence—on the order of past urban disorders, including the 2021 assault on the Capitol. Not a good thing, but something the country could survive. There could be a joker in the deck if the Army went rogue. I suspect the amount of MAGA support in the armed forces is greater than most of us would like to contemplate. But, assuming the Army stays loyal, the violence won’t undo the government.

The bigger problem will stem from the degree of alienation in the larger population. America’s governing structure is unfortunately brittle. It was remarkable for its time, but—with 250 years of knowledge and numerous evolutions in other countries—it is clear that the Constitution is too difficult to change. It binds the country into a process that is readily stalled by a minority and has resulted in an inability to make adaptations that would address some of the fundamental sources of discontent. Given the conservative nature of our legislative mechanics and the degree of underlying division, there is little likelihood of making material changes through the prescribed legislative process. It is too broken.

In short, we are in for a rocky ride no matter what happens in November.