By Mike Koetting February 26, 2024

The last several posts have been on extremely macro issues. Today’s post lurches to the opposite end of the spectrum—local, even hyper-local, issues. I am writing about two specific issues primarily because they remind me how in-your-face cities’ problems are. There is nothing abstract or theoretical about them; they affect our life, up close and in real time. These problems also serve as a reminder of how excruciatingly hard it is to manage cities. Once you put hundreds of thousands of people in a compact space, things get complicated. There are forces well beyond the control of any mayor and most of these problems have no really good answer.

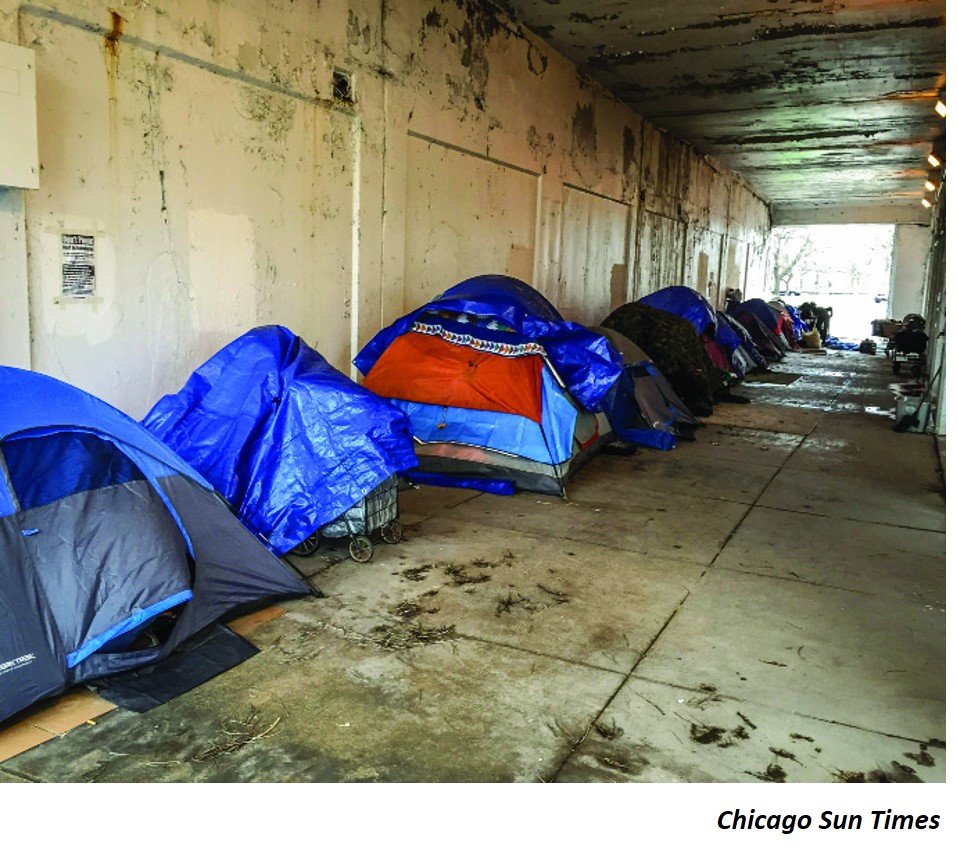

The Homeless Encampment

The homeless encampment under the viaduct a block from our building started right before the pandemic. At first it was just one or two tents, but it gradually grew to about three dozen tents scattered over a two-block area. Initially it seemed like a fairly innocuous reminder of a gnawing social problem. The inhabitants were just trying to live as best they could in an untenable situation. It was slightly annoying to have to navigate around them, but nothing compared to the rigor of living rough. (What do you if you have to pee in the middle of the night? How do you ever shower? How do you stay warm in Chicago winter?)

But as the encampment grew, it became more disorderly. Trash proliferated and the sidewalks became impassible. When it started to get cold last fall, inhabitants jerry-rigged propane heaters—totally understandable, but a danger to themselves and to Chicago commerce, located as they were under the main tracks into the largest commuter station in the city.

Then the rumors started to circulate of drug-dealing and prostitution associated with the encampment. My wife and I were inclined to heavily discount such rumors. While most of my wife’s career has been in violence prevention, she has also been involved in housing and had recently served on the community planning group required for HUD funding to address homelessness. When a petition was circulated in our building urging the alderman to get rid of the encampment, we declined to sign. We were sympathetic with the concerns, but we were also concerned about what would happen to the people. We did not think simply moving the problem from one neighborhood to another was fair or useful.

Eventually it came to a head when one person was shot and killed and, two days later, another was arrested with a gun and a large amount of cash and drugs. Within a few days, the City announced a “street cleaning program” and all the entire encampment disappeared. The city said all were offered a more supportive arrangement and some people took it, but from our distance it was hard to know what exactly happened to the people under the viaduct. (A few tents have since returned. Maybe the cycle will repeat itself, or maybe this is a new homeostasis. TBD.)

Even before the current migrant surge—which has brought more than 30,000 migrants without housing to the city—Chicago was estimated to have 68,000 unhoused people. Most are not on the streets, but it is clear the number who are is well beyond the city’s ability to offer meaningful support. As an insightful New Yorker article describes, such support requires real housing, but must also include robust social services. And, even in the best of circumstances, it is an uncertain business. The problems of the more intractable homeless are entwined with mental health and other substance abuse issues. The literature is clear that, once a person falls victim, these problems feed on each other and are very difficult to overcome. It is necessary that we make much better efforts, but it is not clear where the bottom is for this tangle of messy issue.

I am just as happy the sprawling encampment is gone. But it doesn’t feel anything like success. In fact, it is a bit guilt inducing that there is so little we can do to bridge the gap between our lives and needs of the people in the tents—wherever they are now.

School Choice and Selective Enrollment

While not close in the same geographical sense, this issue more directly impacts our family. Our grandson is in the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) and we assume our granddaughter will follow. The access to high quality education is a necessary ingredient to keep them living in the city. So far, this has been addressed through “selective enrollment.” For selective enrollment, students take a test and the results are weighted by home neighborhood. Poorer neighborhoods get a greater boost to their scores. Parents then apply to various schools and if the student’s specifics match the school’s opening, they are eligible to attend that school. There are also a variety of other special programs available (e.g. dual language, performing arts, etc.) as well as the ability to attend a school outside of your neighborhood. As a consequence, fewer than 10% of high school students attend their neighborhood school. Even in elementary school, one-third the students—like my grandson—attend a school outside their neighborhood.

Recently this system has come under attack by a number of groups, most stridently the Chicago Teacher’s Union.

It is hard to argue that the system doesn’t reinforce existing inequities in our society. Lower income and minority students are underrepresented in selective enrollment schools, particularly the five most selective high schools. Black enrollment at these schools is now around 10% as compared to 35% of overall CPS enrollment. Also, these high schools are located further from most Black neighborhoods and would often require long commutes. The distances for minority communities have become even more of a barrier as CPS has responded to a shortage of bus drivers by eliminating student transportation for most students. Even the complications of getting into selective enrollment schools—learning the rules, getting kids to testing, and “playing the game”—favor families better able to compete in all aspects of our economy.

While I don’t have data at hand, I don’t believe these selective enrollment schools get higher budgets per student. Their primary advantages are the differences in the human resources. The students come from the better-off, many with professional families highly invested in their children’s education. Their kids come to school better prepared and the families typically have other resources, direct and indirect, to enhance their children’s education. If nothing else, they come from families willing to make educational commitments. As a consequence, one of the major benefits of the selective-enrollment schools is that it allows students to be in classes that are designed to challenge potentially high performing students. Thus, while these students represent some attributes that would transfer to other settings, one of the key advantages of these schools is exactly the concentration of these performing students and their families, and is therefore less portable.

Are the school children of Chicago better off if selective enrollment ends?

Proponents of ending selective enrolment say all the schools should be high performing. They further suggest that as students from selective enrollment schools are distributed to neighborhood schools, their attributes, and the attention of their parents, would have favorable impacts on the neighborhood schools.

I have no doubt some of this would happen. Moderating some of the forces that segregate and separate our society is in fact a social good. But I also think there would be much more loss than the proponents are admitting. A material portion of current selective enrollment would not return to neighborhood schools. Some would go to private schools, some to charters, and some families would move to the suburbs. There would probably also be the loss of talented teachers.

Those minority and poor students who currently benefit from being in selective enrollment schools would lose whatever benefits those schools offer. They have already voted with their feet that they would rather be in the selective enrollment schools, often at significant difficulty. Nor is it clear that any distributed gains would be enough to offset the concentrated losses to current selective enrollment students; CPS is a big system and the impact of students distributed over many schools would get diluted. Another issue is that historically the selective enrollment schools, despite apparent White advantage, have been more diverse than the district as a whole. Neighborhood schools reinforce residential segregation.

I don’t know what is the optimal solution from society’s point of view. I certainly hope the selective enrollment schools remain robust and that my grandson gets in one of the highest performing high schools. But I also have some concerns about a system that reinforces existing fissures in our society.

In any event, it is clear this is another difficult set of choices that need to get made. I don’t think I’d like to be mayor of any American city. I am settling for nothing less than philosopher-king. Otherwise, I guess I’ll just keep writing blogs that only require me to talk about hard choices rather than getting in the trenches to hammer out imperfect compromises or slog through the implementation of programs that offer only partial solutions. Perhaps we should spend more time thanking those that do and less time pretending that if someone would only adopt our clear answer that it would solve the problems.

You get my vote as philosopher-king.

Ridiculously difficult topics. I appreciate your tackling them.

Ira Kawaller (718) 938-7812 Check out my blog here: irakawaller.substack.com/

>

LikeLike