By Mike Koetting January 18, 2026

This is the second in a series of posts on how we are bungling the preparation of young people for their lives. Today’s post considers post-secondary education. As noted in the previous post, college student debt is one of the most salient features of young adult society in 2026 America. While this is fueled by the precipitous rise in the cost of college, the bigger problem is that as a society we have misunderstood the economic relationship between college and a good life. This is part of a much bigger problem—what gets taught in college and how—but those are for a different day.

How We Got Here

The problem starts with the fact that historically there was a significant “wage premium” (to use economic jargon) for graduating from college. In the great economic expansion following WWII college graduates did much better economically…and were less likely to wind up in Vietnam.

At the same time, the official US, locked in a geopolitical struggle with Russia, began to worry about the efficacy of American scientific and technical training and engaged in many programs to increase the number of people going to college. It was also a period of starting to address historical divisions in society and one of the politically safest ways to do something was to promote increased educational opportunities as a way of equalizing major income discrepancies.

Then, starting during the Reagan administration, income differentials in the US started to take off. This was due to a series of policy decisions that facilitated exactly such differentials. These policies followed from a set of assumptions about the primacy of capital over labor that led to a significant reconceptualization of how corporations should behave in our society. There should have been a much greater fight over the resulting policy changes since they did not necessarily speak to the well-being of the whole society. Unfortunately, the Democratic Party, the logical–indeed only–group capable of forcing such a reconsideration, itself flirted so heavily with that ideology that no effective opposition was raised.

In light of these, it is hardly surprising that so many people concluded that the best thing for their children was to use college to pole vault into this top tier. By 2010, 94% of all parents of someone younger than 17 said they expected their children to go to college. While that sentiment has cooled a bit, it is still prevalent. It is also the case that with expectations at this level, “not going to college” had a high risk of branding a young person as already a failure.

College enrollments exploded. And, indeed, continues to grow despite increasing levels of skepticism as to its economic worth. I suspect there are a large number of young people (and their parents) who are not at all sure of the returns, but, looking at an otherwise baren landscape, college feels like their only hope.

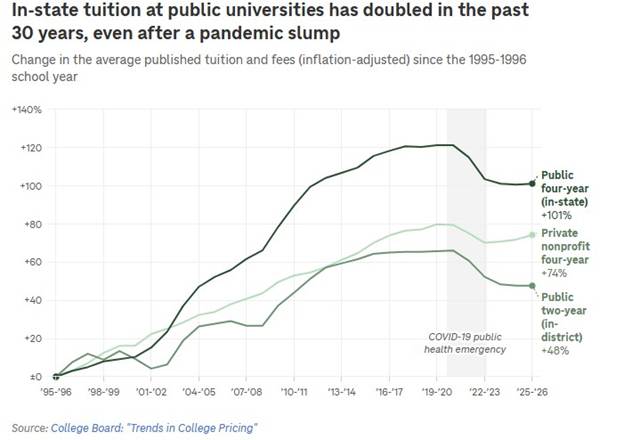

The increasing demand increased prices. There is no shortage of specific explanations for why college prices have increased so much but, for all those reasons, college prices (adjusted for inflation) essentially doubled, even at state schools. (The rate of increase has slowed down quite a bit in the last several years, even shrunk in some cases. But it still imposes very significant burdens on many students.)

College Does Not Guarantee Income

As it turns out, the wage premium for college is by no means guaranteed. Indeed, while statistically there is still a material wage premium associated with college, that measure can be misleading.

In the first place, that statistic applies only to college graduates. Depending on the measure, between 30% and 50% of students who start college never graduate. Which, unfortunately, does not insulate them from debt for money they borrowed to attend what college they did. Graduation rates are strongly correlated with race, gender and income. Hence, the odds of financial betterment through college drop for poor, non-white and part-time students.

Second, the overall average wage-premium is significantly impacted by the inclusion of outliers in the top income tier. Across the whole spectrum, the results can be very different by person. A study from the HEA Group of nearly 3,900 college graduates found that for 40% of college students, the wage benefits were either a wash or actually negative once the cost of attending college is taken into consideration. Thus, for some, particularly for kids who started off economically disadvantaged, college made them poorer.

This outcome was predictable. A while back, college degrees were valuable in part because they signified a rare degree of accomplishment, sometimes specialized knowledge. But a decades-long surge of college graduates has oversaturated the market, diluting the value of the degrees and turning what was once an advantage into table stakes. As many as half of all college graduates wind up in jobs that do not require a college degree, many of which do not pay that well.

Moreover, to the extent that the nature of income has slanted from labor to capital, college adds large benefits primarily to the extent it increases access to capital. This does happen. People get training or ideas are sparked that lead to entrepreneurship or some other specialized niche that gives rise to the rewards of capital. But that is hardly typical. In too many cases, college consolidates privilege rather than creating paths into prosperity.

All of this has psychic costs as well. Good high school students worry endlessly about whether they will get into one of the “magic ticket” colleges. High school students with mediocre academic aptitude worry about what will happen to them—and wonder whether their life-chances have been diminished before they are 18. And some kids simply don’t want to go to college, but how do they exercise that impulse without being made to feel like a loser? And how does it feel if you are one of the many college graduates to be underemployed, having spent time and money (some of which still has to be repaid)? And all of this with a patina that implies whatever happens to you is somehow a real measure of your worth to society.

The Other Side of the Coin

At the same time as we have put a too large portion of the population on an expensive escalator to nowhere, we have neglected support for other kinds of jobs that used to provide good lives and in many cases still do. There are skilled trade positions which are both in high demand and provide greater income than many college graduates are able to earn. Estimates of how many jobs require training beyond high school but not a college degree—so-called “middle skilled” workers– vary by source, but it could be as high as half of all jobs. This measure is also confounded by “degree inflation” because employers are requiring college degrees for positions that did not previously require them.

However measured, in many middle-skill categories, job openings outnumber appropriate applicants. McKinsey analyzed 12 types of trade job categories, including maintenance technicians, welders, and carpenters, and predicted an estimated imbalance of 20 job openings for every one net new employee from 2022 to 2032. Walmart has been so stymied its quest to fill middle-skill positions, it has launched its own training program.

One other interesting note. Skilled tradespeople report themselves as on balance happier than the average worker.

Where Does This Leave Us?

As usual, easier to see problems than feel good about solutions, even when it’s rather obvious what needs to be done. For instance, one of the more obvious is to rearrange our economic structure so that young people (and, importantly, their parents) don’t feel their only hope for a good life is to go to college. While it seems to me that appetite for changes of this magnitude is growing, I don’t see it happening quickly.

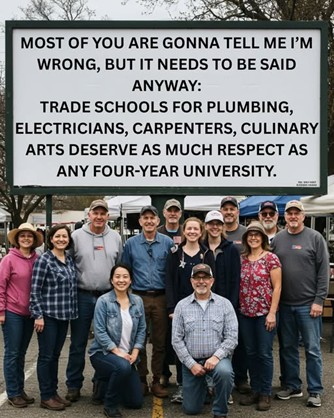

Related, I don’t see the cultural “over valuing” of college changing quickly. I am not knocking college. Indeed, I can make a compelling case why college for all, properly structured, is a good national policy. But not the way we do it now. There needs to be real cultural acceptance of the idea that there are many routes to happiness, and some of them are through trade schools and other training.

I frequently see postings on Facebook very much like this one.

What really strikes me about this post is that it starts out so defensively. I suspect that support for this position goes a whole lot deeper than the authors of this post assume. The consciousness that we have pretty much made a hash out of the postsecondary needs of our young people is growing.

That said, this general level of support needs to be translated into specific policies. The Biden administration was able to increase support for technical training and there were some modest new supports in the budget bill. But there have also been some backslides and random shorts. Thoughts about how support could be more robust might better target money and accelerate the culture conversation about the value of various career routes.

We also need to completely rethink how we want to fund post-secondary education, from the perspective of both the colleges and the students—and other needs of society. That, however, will be a huge lift in a culturally littered battlefield. There are also whole ranges of problems with colleges and college education that I didn’t even touch on in this post.

Two small things that might help, although they are kind of band-aids to the inadequacy of the current situation. We should improve financial literacy training at all levels so that kids might have a better idea of what they are getting into when they decide to go to college. (It will be hard to make this effective unless their parents are being exposed to the same information, but communities can do what they can.) Second, we need to make sure that high school guidance counselors understand the issues about college choices and actually can convey these to students (and, again, hopefully their parents).

Given the current situation, mostly what I have to say to the kids now in high school is “Good luck dealing with the mess we made.”