By Mike Koetting August 5, 2025

Today’s blog is the first of two posts about AI. It’s not about whether AI is good or bad for society. That’s a worthwhile discussion and the answers likely to be endlessly debated. But these posts assume that, like it or not, it’s coming. (Whether it lasts or not is a different matter, but we’ll get to that later.)

The point of these posts is to ask some practical questions about its arrival.

Risk #1: Blowing up the Economy

It is interconvertible that AI will have material impacts on the economy. We don’t know how large those impacts will be, how they will be distributed, or what will be the secondary impacts.

Optimists typically offer some version of: ”Well, there was all this disruption with the onset of the Industrial Revolution and look how much better our lives are now that the dust has settled. This too will eventually work itself out.”

They could well be right. AI contains huge possibilities and humans have been remarkably successful at adapting to technological change. But there are no guarantees. Estimates of how many jobs will be lost to AI are all over the place, so specific numbers are only propaganda. But imagine what happens if unemployment were to rise to, say, 15%, slightly higher than the worst rate during Covid. Is that acceptable to the general public? During Covid, we knew the problems were primarily in disruptions of the supply chain; once we got those straightened out—and added supports to keep the economy from cratering while that was happening–the rate fell sharply and quickly. But if AI creates real structural changes, and there is plenty of reason to think it might, maybe the 15% rate would be permanent. Or, at any rate, take a long time to work itself out.

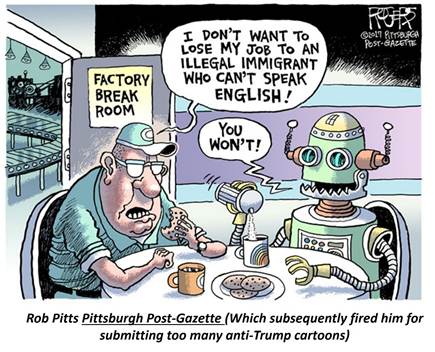

And even if all is eventually rosy, being part of the collateral damage as we go through this transition will be really unpleasant. We have seen what has happened as automation and outsourcing de-industrialized parts of America. It was ugly and I don’t think there are many people who believe our society handled that well.

It’s not clear where AI will have the biggest impacts on jobs, but there is evolving consensus that the most immediate impacts are on people seeking entry level jobs, even those who thought they were playing by the rules by graduating from college. I have yet to see any solid argument about where the replacement jobs will come from. There’s only room for so many TikTok influencers.

It’s all well and good to say that in the long run it will work itself out. Not only is that uncertain, but I have noticed a distinct lack of volunteers to be sacrificed for the glorious future of AI.

Hovering on the precipice of this big change, I believe government, as an instrument of society, should be doing something besides shrugging its shoulders and saying disruption is inevitable. It is time to invest some serious resources in imaging alternative scenarios. I am emphatically not suggesting that government should try to “plan” the economy. (That will be the first thing people who don’t want anyone raining on their gravy train will say, citing Russia, China and so forth.) Rather I am saying that some resources should be invested in thinking about how we will respond if there are major dislocations in the employment market. It’s not too early to build some awareness among policy makers of the risks and possible directions of responses. I think it would be very instructive if we could get half of Congress to actually think about what would be a response if we were losing a net 2% of jobs per year to AI.

The entirety of our social structure is built around people working. It is surely the case there are theoretical alternatives, but it is also screamingly the case that the U.S. is nowhere near ready to address those. The amount of rhetoric about “got a job” from Republicans during the budget debate—as they were reducing benefits for the disabled and seniors—suggests the distance. Addressing this issue will require more than money; it requires reinventing our national image of what a well-lived life looks like.

A second economic consideration is the sheer amount of money being poured into AI. So far, in 2025, Big Tech has invested $155 billion in AI. While numbers that big are so abstract that we typically don’t really think about what that means, perhaps better perspective is gained by noting that is more the US Government spent on education, training, employment and social services combined over the same period. Statements by corporations suggest their investments will be even larger next year.

At one level, that’s fine. Corporations can spend their money on whatever they want and there may well be spectacular returns to both corporations and society from these investments. Still, this is a huge bet. If it goes wrong, it will have pretty serious impacts on the economy. But if it goes right—AI works out as anticipated—it will put stunning amounts of economic (and therefore political) power in the hands of a few corporations. Is this really healthy for society?

A totally related consideration is how the rise of AI will change the distribution of income. In theory, it would be possible to structure the distribution of income so that there is greater equality in the prosperity generated by AI. But the losers would be in a very poor bargaining position. As we have been seeing for the past 50 years, the owners of new technology are eager to keep as much of the benefits as they can. Early evidence suggests this trend is continuing and acceleration of AI is making incomes more unequal. There is no reason to think it would be different if AI accrues even more power—unless specific measures are taken to achieve better balance. The economic tools are known and available, but at least until now, political will has been lacking. It is not in the long-term interest of the country to cater to the desires of corporate monopolies and the super-rich they have created at the expense of the other 90% of society.

But the Republicans—and some Democrats—don’t seem to believe that.

The next post will consider environmental issues and questions of security and reliability.