By Mike Koetting July 8, 2025

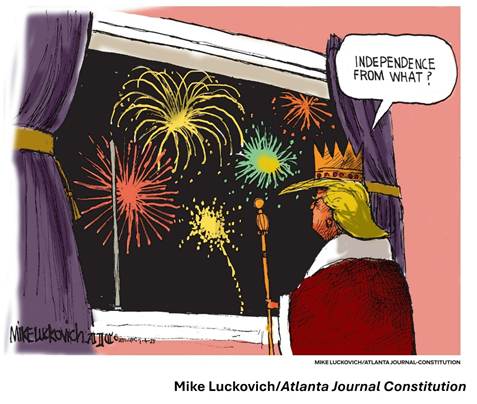

Another Fourth of July rolled around and there was new grist for the perennial question of how I feel about being an American.

Being an American is, foremost, a legal definition laying out certain rights and responsibilities. Becoming an American was easy for me: I was born here. And since, at least so far, I haven’t wanted to leave, I am still an American. Of course, the legal fact doesn’t shed light on how I feel about this.

At one level, how I feel about being an American is kind of an unconscious, automatic response to being part of a group, a community larger than me. I always cheer for American teams to win in the Olympics. There are also certain patriotic tropes and evocations that never fail to move me. Lincoln’s Second Inaugural address, for example. Or Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land.” I suspect this deep-seated sense of “home” will stay with me no matter what.

But these group instincts are nowhere near as important as the more analytical view of what I believe America stands for and how that is being realized, or not, at the moment.

For me, there are a core set of values defining what government should do and how it should do it. America, through outstanding individuals and as a nation more or less united, has probably done more than any other nation to both define these principles and show how they can be implemented. Not that this has been a straight or easy path. At every point in our history, we made mistakes and failed to live up to our own values, frequently in deviations so stark as to make you shake your head. I don’t need to repeat that litany. But sooner or later, we eventually got closer to those ideals, even if not all the way there. I don’t know if “love” is the right word for my attitude, but I am passionate about my support for the “better angels” of our values.

At any given moment, however, the core ideals are subject to how they are being implemented. Here’s where things get messy. The core ideals are less a set of specific prescriptions for government so much as a set of “rules of the road” for how to run a government that provides for liberty and pursuit of happiness. The essence of these rules are, first, that all humans have inalienable rights, some spelled out in the Constitution very specifically; and, second, that spreading power in democratic institutions best protects against tyranny of either a ruler or the majority.

Since these are only principles, there are always disagreements about how exactly to implement them. Which is fine. All configurations require trade-offs and a democratic society needs to continually debate those trade-offs. As much as I sometimes wish otherwise, I accept that few positions are unequivocally correct, even my own.

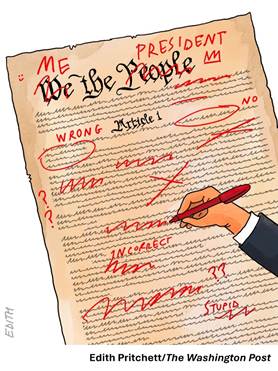

By the same token, there are limits to my tolerance. There are some things that so violate my sense of the principles that I believe they are un-American. The Trump administration, supported by a cast of Republican enablers, are like a bunch of five-year olds just seeing how far they can go toward violating these principles before they are stopped. They see the distribution of power across institutions as a check on their unbridled power and they obviously are willing to assume away the humanity of migrants.

These are not disagreements about policies. These are questions about what a country means—about what principles are at the core of the collective agreement to be a country. I got through the Vietnam period of American life vehemently and actively disagreeing with the government but never doubting that the fundamental principles of the country would reassert and, indeed, relying on the protections these principles afforded as I went about opposing it.

But I no longer have that confidence. Michael Luttig, a Republican appointed judge and a protégé of Antonin Scalia , marked the Fourth of July by enumerating how the policies and aspirations of the Trump regime echo the 27 grievances the colonists listed against King George in the Declaration of Independence. Luttig writes elsewhere:

The president of the United States appears to have long ago forgotten that Americans fought the Revolutionary War not merely to secure their independence from the British monarchy but to establish a government of laws, not of men, so that they and future generations of Americans would never again be subject to the whims of a tyrannical king….These constitutional obstacles to a tyrannical president have made America the greatest nation on Earth for almost 250 years, not the fallen America that Trump delusionally thinks he’s going to make great again tomorrow.

This leads to a form of political schizophrenia—where, on the one hand, I am deeply committed to a set of principles about the America I want and, on the hand, I find myself living in an America that is pretty far along the road to being ruled by a diametrically different set of principles.

This means I have to rethink what it means to love America. At some point America is no longer the country into which I was born but is an imposter fraudulently using the name.

I am not sure what then. My current thought is that as long as Trump does not openly defy the Supreme Court or blatantly mess with the elections (including peaceful transfers of power) then I can continue expressing opposition through protests and supporting legal and political challenges.

For me and many of my friends this does not seem enough for something that so violates our core sense of country. I am particularly conflicted about the fact I find myself hoping for various communal setbacks—economic reverses, shortages brought on by lack of migrant workers, community and individual health concerns as a result of Medicaid cuts, environmental disasters in Red states—since it seems that only really tangible hardships will get enough voters to care about the more abstract, but long-run more important, principles of how we govern ourselves. This is why the Founding Fathers wanted to make it hard to change the core principles.

These set backs are also reminders that authoritarians, no matter what they say, don’t care about the people. All history shows that in the end they care only about themselves. If people want to improve their lives they need to trust democracy, even if it is contentious, sluggish and sometimes makes mistakes. Over the long haul, it works out best for everyone.

In someways, this attitude is the ultimate condescension. In other ways, it is the reality. I firmly believe that the Congress people who have given away these more abstract principles know better. Whatever other concerns they have, they know what are principles and what are merely policy disputes. In surrendering these principles, they have twice betrayed their country because they have made it almost necessary to root for the worst.

If Trump crosses my hard lines, which unfortunately I do not believe impossible, I will be marooned in a country with which I have profound ethical conflicts. I’ll have to decide how far I am willing to go in my resistance. I don’t think America will ever get to the situation of Russia where I will fear being sent to prison for my blogs, so I’ll continue to write them. Would I if I faced Navalny threats? Who knows. (That might get more attention than the blogs themselves are capable of generating.) Would I emigrate? Would I encourage the kids to emigrate? There are countries elsewhere in the world that are holding to the principles I want to associate with America.

It would, presumably, be easy enough to keep my head down and live out the years left me. But wouldn’t that be the ultimate failing to love America?