By Mike Koetting May 7,2024

I’m a religious reader of the articles published by Bob Melville in The Civic Way, a much more disciplined look at policy issues than my own scattershot set of interests. He has recently undertaken an excellent multi-part series on the challenges facing public education. It’s not a cheery read because public education is facing crises from multiple directions.

His piece on “The Public Teaching Crisis,” however, touched on a couple of my hot buttons, so I thought I would offer some suggestions as to how I would explicate and implement some of his thoughts. These proposals reflect my fundamental beliefs not only about teachers, principals, and educational quality, but also underline broader sentiments on doing the public business, which is much more complicated than people want to accept. These, however, are my own ideas and you can’t blame Bob for them.

Defining Educational Quality

Americans are generally unhappy with the direction of our educational system. However, descriptions of what is wrong vary so much by political ideology, one must assume a fair amount of this dissatisfaction is simply another refection of the broader societal malaise. People would like to imagine that education could fix whatever it is they think wrong with society—around which there is little agreement and much passion. But it will be hard to get public acceptance of education until we figure out how to address the broader disentrancement with our society.

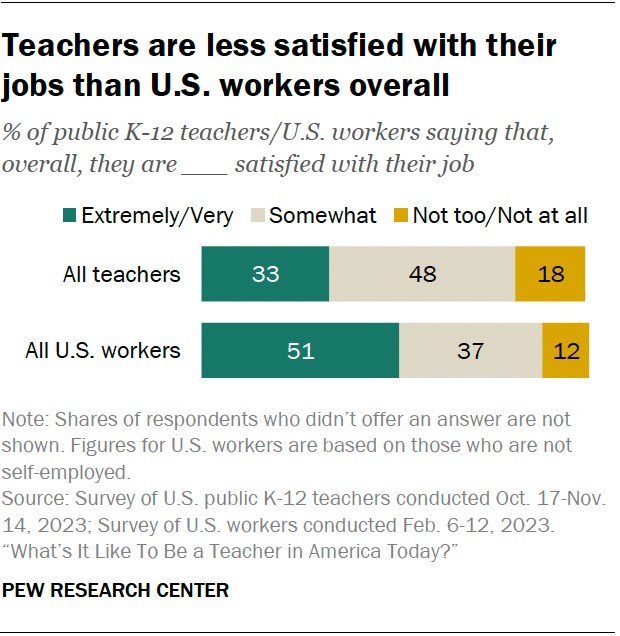

In the meantime, this malaise combines with factors more specific to the educational environment to create a high level of teacher dissatisfaction.

What’s causing this dissatisfaction is presumably what’s at the root of the looming teacher shortage.

Part of the societal dissatisfaction with education stems from unrealistic expectations. We ask a lot from our schools. While pre-college education sometimes gets presented as acquisition of specific skills or attitudes, what we really want is for schools to prepare young people to live their best lives and to be useful members of society. These are tall orders. While schools absolutely influence how this goes, they are minority contributors. A larger percentage of the outcome for any particular child is due to factors beyond the schools’ control. It is all too easy to equate quality with the outcome without taking into account the students’ larger context. Most of the schools we think of as “high quality” started out with students who were in one or multiple ways advantaged. While these schools are often able to multiply those advantages—which is why they are appropriately valued—their starting line is dramatically different from other schools.

Moreover, consistent with the breadth of what we want from schools, there are many dimensions on which a teacher can foster—or fail—a student’s journey toward adulthood. One teacher might do a great job at instructing on basic grammar, another help students develop analytical capabilities, another provide outstanding guidance in the importance of empathy in human affairs, and another have the ability to see students with particular potential and light a fire that takes them to great heights. And yet another, have the ability to understand in a special way the personal difficulties faced by students and help them surmount those difficulties. It is unrealistic to expect every teacher to be good at all of them.

Consequently, I am deeply suspicious of any one size-fits-all evaluation system.

Which is not to say either that evaluation is impossible or that it should be ignored. Quite the contrary; effective evaluation of teachers is essential. However, it must be approached with flexibility and humility and acknowledge the multiplicity of goals inherent in the process. And it must accept the risk inherent in a certain amount of “messiness”. The more complicated a desired outcome, the more difficult to evaluate efforts to get there. One of the many pitfalls of system management is to overvalue things just because they can be concretely measured.

If It Were Up to Me

In the first place, I believe in giving a huge amount of discretion to principals. The principal must be the CEO of the school and should have ultimate hiring, firing and promotional power. They must articulate the vision for the school and see it as their responsibility to identify, nurture and retain those teachers who best contribute to the overall endeavor. And I believe that only someone on the spot can make the many tradeoffs in deciding who contributes appropriately to the team and who doesn’t. They are also the ones who must facilitate the critical job of using what resources are available—including the teachers themselves—to make the most progress.

Appropriately, principals are chosen by the central administration. And they should be chosen less on credentials and length of experience and more on the ability to create a school that fires on all cylinders. Principals should get multi-year contracts but also get annual multifaceted evaluations and resources to address identified concerns.

Like principals, teachers should receive a multi-year contract. I am not a fan of tenure for K-12 teachers. It’s not because I’m focused on the bad teachers out there or that it is sometimes too difficult to get rid of them. Both are obstacles and need continual attention. But I don’t think these are the major problems with our educational system. The role of bad teachers (and teacher unions) has been greatly exaggerated in the public mind. Unfortunately, the problems are much more systematic, many of them stemming from our society’s lost concern for communal welfare. I think we will do better focusing more on helping all teachers do better while we are waiting to fix society’s many other ills.

Nevertheless, I do think the structured, periodic consideration of a teacher’s employment status will encourage teachers to maintain their edge. In my mind, one of the most important features a teacher brings to the classroom is energy. Not necessarily physical energy, but emotional and intellectual energy. A huge part of teaching is really sales. Most people do not appreciate the amount of energy it takes to be “on” so many hours of so many days. If a teacher is no longer capable of providing that, or no longer has the ability to effectively connect that energy to the classroom, they should be in a different profession.

As a partial safeguard against arbitrariness on the principal’s part, I would require that decisions about renewing contracts be made by a committee that includes teachers who would be elected by the school’s teachers to serve multiple year, staggered terms.

Regular evaluation of teachers would be an important part of this process–both to help them improve and to provide standards for retention and salary. This means observing, listening to parents, doing some survey of students—would obviously differ by age—and considering standardized test scores. The real world has real standards of knowledge and skills needed to achieve most kinds of success; part of the goal of schools is to impart those. How successful a teacher is at imparting those skills is an important part of their job. Where students start is critical in understanding the actual contribution of the teacher. But it does no service to students to give up on standardized test achievement because they have farther to go to do well.

However, this should not extend to using some straightforward formula tied to standardized tests to determine teacher compensation. Important as they are, standardized tests measure only one dimension of the growing-up process. Overstressing them warps the system.

Interim evaluation of teachers has to be more than checking off items. The process should be around helping teachers improve their craft. Schools will need to invest in people who can really help teachers be better, particularly beginning teachers. This will probably require a special skill in its own right, including the willingness to listen to teachers as to what they actually need and what they see as the main obstacles to improvement. It will be important to have teachers themselves involved in the process. For instance, Milwaukee had a program where a struggling teacher would get a more experienced mentor (who got some released time) for up to two years. Apparently, some teachers rose to the challenges, and some didn’t. But, if at the end of that time, the teacher was still not making it, there was some communal sense about the problem.

The Role of Teachers Unions

I sympathize with the reasons for teacher unions. For years, society drastically underpaid teachers, in part, I suspect, because it was a profession so heavily dominated by women. And, despite some advances in recent years—almost all in response to unions forcing the issue—many teachers are still underpaid. It is likely that even higher salaries would be necessary if we actually did reduce job security and adopted more systematic ways of identifying the best teachers

I don’t think the consequences of teacher unionization are anywhere near as catastrophic as some portray. But it is problematic that the union model assumes once a person is hired, their subsequent contributions are all equal—and best measured on a scale of longevity or educational preparation. Moreover, the underlying fear that anything not specifically negotiated is disadvantageous gets in the way of needed flexibility. I believe that the current fascination with using standardized testing as the main, even sole, means of evaluation is a predictable response to the teachers’ unions use of industrial approaches.

Even with a less direct role in salary negotiations, there are important roles for teachers’ unions. For one, they provide necessary muscle in reminding society that we need to invest in education. This is important; people have short memories. In my proposed world, the unions could—and should—be a voice in monitoring the risks of less rules-based approaches. Some of that could be served by monitoring the results of personnel decisions and by providing resources for teachers who felt they had been abused by a principal’s decisions. And they would have a clear role if there was a collective sense that the principal was operating too far outside acceptable variations. If necessary, this could include assembling a case for the central administration.

This would still leave open the possibility of friction with the principal but on balance I think it would be beneficial: it would encourage teachers to take a broader view of achievement in the school and principals to adopt courses of moderation and cooperation. Much more than in corporate settings, the teachers and the administration have a common goal—education of the next generation.

Perspective

While these suggestions probably include something everyone can find to disagree with, they reflect my more general ideas about government policy. We have tried so hard to make things antiseptically rules-based that we often run the risk of making the perfect the enemy of doing anything. We must accept that with all really complicated issues, perfect solutions are not possible. We give lip service to that reality, then proceed to lock ourselves into struggles as if that were not the case. I believe humans are in fact capable of finding some more cooperative middle paths. Education might be a good place to start because, despite real differences, there are people of good will and common goals on all sides.