By Mike Koetting February 13, 2024

My last post suggested that at least some of the premises underlying specific political and policy decisions are based on assumptions about reality that are increasingly questionable. Today’s post considers what it would take to establish premises that might better fit evolving circumstances.

Two comments before I jump in:

- Despite the reality-erosion of the old framework, am not suggesting there is any likelihood of new premises being adopted any time soon. Would it be nice if we could get there sooner rather than later? Absolutely. Is there any chance? Not that I can see. The idea of limitless resources and growth is simply too embedded in our psyche to become an element of policy unless changing conditions actually force it.

- If that’s the case, why discuss? I believe if it does really hit the fan, the more thinking we’ve done about alternatives, the better off we’ll be. Of course, it is impossible to predict with much precision the way in which change will eventually be forced. Still, better to have starting places if you are trying to re-assemble the jigsaw of a global economy based on fossil fuel that is falling apart and you’ve squandered the opportunities for a more gradual transition. It could possibly be the case that as people start to think about how different principles might be incorporated into policy—someday—it may increase the ways into which these ideas can leach into the body politic. Perhaps even create some rallying points for future political action.

That said, I offer the below considerations as we develop a new framework for forging specific policy choices.

Accept that Economic Growth Is Limited

Hard as this is to even conceive, this is likely the new lynchpin. I suppose it is possible that mankind could find some ways out of the bind by coming up with some truly sustainable, renewable energy sources that rely on otherwise abundant materials and don’t create a hazardous waste nightmare. Mankind is endlessly inventive. Who could have imagined the world we live in today 200 years ago or even 100? I wouldn’t want to discourage anyone from trying.

But as we sit today, there is no such thing and a shrinking time line. If developments proceed as climate scientists imagine, it won’t be long before there is less choice in the matter than anyone would like. The sooner society accepts slower growth as a principle—that is to say, when politicians can talk about this without being rendered irrelevant—the better. As long as we cling to the idea that economic growth is necessary, our politics will be warped by the contradiction between that and the physical realities of the planet.

Not that growth is without benefits. Economic growth has been responsible for the great expansion in human freedom and fulfillment that started with the Enlightenment. This expansion continues to ripple outward. Previously, economic resources were primarily land. If you had some land, you had some freedom. But it was largely a zero-sum game since the amount of land is finite. When people started to move to cities and create other dimensions of wealth, ideas of freedom and human worth started to expand. In the centuries since, that pattern has continued: people’s ideas about what it means to be human, about what inalienable rights any of us have, expand when economies grow. What happens to these ideas of human possibilities if we eschew economic growth? It is not clear the advances secured so far can survive economic stagnation.

How Do We Do It

Beyond the slogans about less growth, the reality is that we don’t know how to do this. It isn’t even a little clear how we would organize an economy based on zero growth. In some aspects, the market will decide. If the cost of some goods become prohibitive, people will use less of them. But what principles will we use when things start to fall apart? In a world where air travel is three or four times more expensive, there will be many fewer flights. What happens to people who are currently servicing those flights—from building airplanes to loading luggage? And how will the ensuing losses be apportioned between ownership and labor? Will people who can afford it be able to fly with no limits? (Taylor Swift apparently used a private jet to fly from her concert in Tokyo to the Super Bowl and then back to her concert in Australia. This is estimated to be responsible for more carbon emissions than six average Americans use in one year. And that’s a comparison to America; comparisons to Africa would be somewhere north of 75 individuals in a year.)

I suspect we will want to set limits on how much will truly be left to the market. One part of achieving that will be serious income redistribution. If the extreme rich have less money. there will be lower demand for resource-burning luxury items. But even if more redistribution becomes politically feasible, a prospect I’ll return to momentarily, there are other questions. One of everyone’s favorites is how would that impact the rate of innovation? In my mind, the issue is not so much at the level of innovation itself—innovators make breakthroughs more because of intellectual curiosity than the lure of a large payout. The real rub will occur in getting from idea to practice. Often, particularly in the US, that requires sufficient capital to fund start-ups. Investors are looking more for return than intellectual satisfaction. If there are more obstacles to scaling up new projects and more taxes afterwards, there will be less innovation.

Part of me wants to say, that’s fine. That’s what we mean by less growth. But the other part of me says, wait, what if those innovations were really useful in getting us out of this situation or making life better for everyone? We typically talk about taking risks to implement. Now we may have to consider the risks of not implementing things. It seems likely that unlimited innovation is too expensive for our future, so we will have to learn how to innovate strategically.

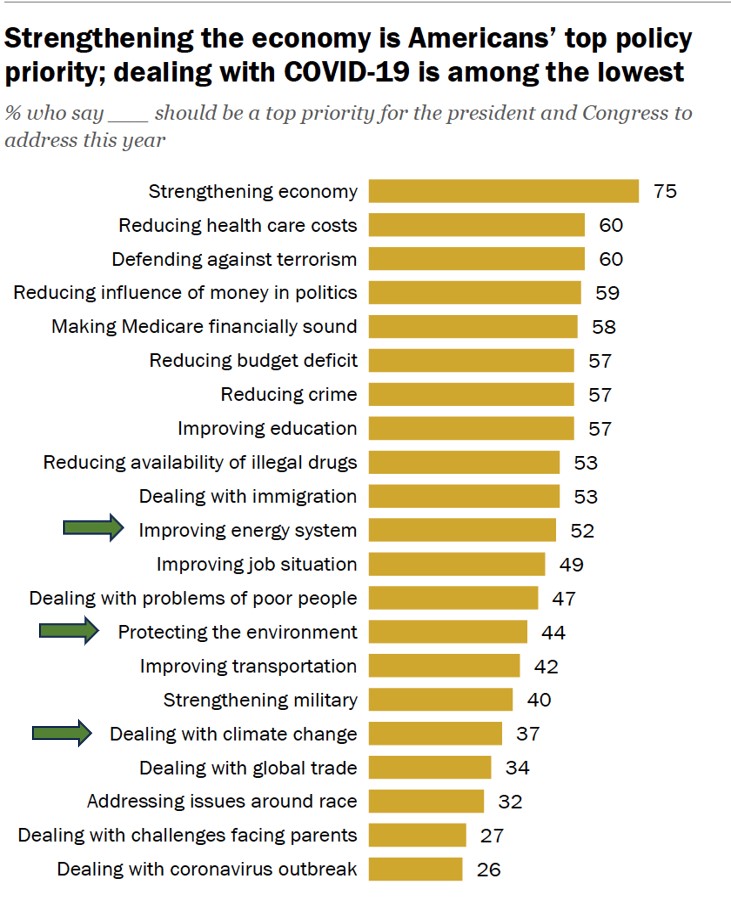

Which raises the question of how we do determine the highest priorities. Excluding Taylor Swift’s private airplane is relatively easy. But ensuring our resources are directed at things that are most broadly beneficial is more difficult. There is a general consensus everyone should have food and shelter. However, in America we are doing only a mediocre job at guaranteeing that for all our current citizens, let alone those who endeavor to come here. It is not obvious how we would even decide what are the minimum standards to which “everyone” was entitled. Then we would have to live up to those standards, possibly made even more difficult in a world challenged by faltering resources and increasingly difficult food production.

Scotland is attempting to broaden its fundamental measures of national performance to include a wider range of measures of the overall wellbeing of the society. It still includes measures of economic growth, but it also includes measures of carbon emissions, food insecurity, housing costs, wealth inequity and child wellbeing.. Among other things, this makes concrete the trade-offs among different priorities. Others looking ahead may want to borrow from this approach to get beyond the stranglehold GDP measures put on the political framework.

If we don’t find a way to focus on meeting human needs more equitably, the world will become very ugly. I don’t know how truly passive peasants were in the Middle Ages, but I don’t think the poor will be willing to go back to that status without one hell of a fuss.

All this implies some kind of planned economy. It is hard to any find much favorable press for planned economies. To the extent the criticism of planned economies is focused on their relatively slower rate of growth, under evolving circumstances, this might not be so much of a problem. But the more fundamental problem is that planning for everything is impossible—and attempting to do so gets bogged down in hopeless bureaucracy.

So, somehow, we need to find a way to actively manage the economy without suffocating it. No one knows exactly how to do this, but one thing is certain: if we approach this with a Manichean view—that one or the other is all good or all bad—it isn’t going to work. We will need to invent an approach that puts broad guiderails around the economy, but allows appropriate market freedom within those.

Income Redistribution

An essential element of getting to there will be substantially more redistributive taxing and spending approaches than currently in place. It is my belief if there were a plebiscite on higher taxes on the rich and more redistributive spending, it would pass. But we don’t make policy that way. There are too many points of veto in our current system with plenty of people willing to pull those levers. I have to believe that some point it will become impossible to ignore the gaps between what as a society we need and how our political/tax structure obstructs that. But the fact I believe something doesn’t offer much comfort. And I could be dead wrong; maybe the rich of the world will ride their advantages all the way to the end, squeezing everything possible out of what remains.

The apparent willingness of so many people to prefer Donald Trump’s authoritarianism over democracy and redistribution shows people vote less on issues and more on some constellation of emotions that skip specifics altogether. For many Trump supporters, positions that are anti-immigrant. anti-woke and sometimes racist are much more important than other stars in their political constellation. Thus, Blue Collar workers clearly getting screwed by giving more tax breaks to the richest come to believe that is acceptable, even desirable. The same thing is happening in Scandinavia, where the historic commitment to redistribution is waning with the arrival of immigrants. Once a society divides into “us” versus “them,” other ideas lose potency.

How all this will play out in America will be a lot clear one year from now. For better or worse, however, neither a Trump nor a Biden victory will stop the rate of environmental change. Oil will still be used and temperatures will still increase, both at unsustainable rates. Whatever happens, we will need a different set of underlying policy principles. We have a lot of work to get there.

****

Editorial Note Today’s post (and the last one) are materially indebted to Steve Genco’s two part post on Medium “Why We Need to Grow an Ecosocialist Party in America” To be sure, I go somewhere fairly different than his ideas, but I still found them quite useful. His posts are consistently interesting, although they make me look like a cock-eyed optimist.