By Mike Koetting January 16, 2024

Today’s blog stems from my own feeling of disorientation as I contemplate the distance between some of the most spectacular knowledge ever achieved by humans and the risks to life as we know it from the application of this knowledge.

Some advances are truly dazzling. They can be seen only as magic to all but a handful of experts. My mind is blown by the fact we can identify a tiny strand of chromosome, understand its function and then manipulate it. Or that a computer can listen to a Zoom call and provide a workable summary of the discussion in multiple languages.

The application of science and technology inevitably results in changes to “life as we know it”. But how much change do we want? And, even if we could agree on the answer to that, how confident are we that we can limit change to within those boundaries? Or, perhaps, even if pushed beyond where we intended to stop, that we will be able to adapt to where the chips do fall?

It seems distinctly “fogeyish” to even bring up the fact that consequences of any particular change could spiral out of control. One of the characteristics of the last several hundred years has been to ignore multitudes of warnings about the impact of major changes. These changes, although typically launched without fully anticipating the consequences, have not destroyed the world. Local cataclysms, for sure. But on balance, the scientific and technical advances of the species have had a remarkably favorable impact on the quality life. Material life has never been better, especially for those in the global North.

But what if this is simply a reflection of how little time has transpired measured on a planetary scale? Or, perhaps, of how relatively little we have pushed the system. Time goes by and each advance builds on the previous, potentially magnifying the consequences of unexpected changes. Still, I look forward to the positive applications that might come from these changes.

I am not sure how all of this factors into policy, but it does seem to me understanding the possibilities and risks is more important than so much of what gets discussed on a day-to-day basis, so I want to take a quick look at two areas where I am particularly caught between awe and fear—gene editing and artificial intelligence.

Gene Editing

Just before Christmas, the FDA approved Casgevy—a drug/treatment regime that shows potential to cure Sickle Cell Disease. This is the first approved, applied use of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) or gene-editing as it is more commonly known. It is a watershed moment

Sickle Cell is a horribly painful disease that occurs almost exclusively among Blacks. About 1 out of every 365 (.28%) Black babies born in the US is afflicted. Almost anyone in the Black community knows someone debilitated with the excruciating pain. There are still major technical issues to be worked out, but if history is any guide, these issues will be surmounted. There is the real possibility of a cure. For the afflicted, this is a major cause for celebration and reflects the absolutely best aspects of our biomedical enterprise.

There is, however, the obvious issue of cost. It appears the U.S. cost of each procedure itself will be roughly $2.2M, which does not include the weeks of hospitalization required. The problem is not that this is necessarily a bad bargain, even from an economic perspective. A report by the nonprofit Institute for Clinical and Economic Review said prices up to around $2 million would be cost-effective. This follows from research earlier this year that showed medical expenses for current sickle cell treatments, from birth to age 65, add up to about $1.6 million for women and $1.7 million for men. But lifetime expenses are spread over a long time period. Doing them all at once is a different matter for people who pay. Moreover, a very high percentage of Sickle Cell patients are covered by Medicaid, which makes it a very visible policy issue. And all of this is before considering the fact that there are millions of Sickle Cell victims in Africa. The odds of making any dent on that in the near future are miniscule, but it creates a series of thorny moral choices.

There is another issue, both more abstract and potentially more far-reaching. This is the first approved medical procedure to incorporate CRISPR. This particular application has been well discussed and its development proceeded in full view of the scientific community; there is abundant reason to believe the benefits outweigh the risks. But there will be other applications. In opening the door to CRISPR use, it also opens the door to all kinds of problems with CRISPR. These include technical issues (what happens if there is an editing error, are we sure we understand all the longer run and ancillary impacts) and ethical concerns (will resource inequity be encoded in biology, will this slide into a form of eugenics).

None of the above is an argument for not proceeding. Advances typically come with risks. But it is a reminder that as our knowledge continues to expand—into realms so incredible that it is hard to think about them—the potential disjunct between what we know and actual human behavior is growing exponentially. At the same time I am celebrating, I am also enormously wary.

Artificial Intelligence

It’s hard to imagine there is anyone in the United States who hasn’t been inundated in news stories, discussions and shows about AI.

Most often discussed are business applications. The new Copilot applications being gradually released by Microsoft can perform a whole range of office functions that last year required human intervention. The ability of AI to write computer code has increased multifold in the last few years. This is miraculous stuff.

Less prominent in the discussion, but perhaps more impressive, has been some of the other benefits of AI. For instance. a recent project at MIT used AI to identify new antibiotics that would create a potential cure for MRSA (methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus), a deadly infection that kills about 10,000 people a year in the U.S. alone. Their work used AI to identify chemical structures that are associated with antimicrobial activity and then sift through millions (millions!) of potential compounds to estimate which ones would have strong antimicrobial activity against specific bugs.

I’m in awe. But again, the concerns.

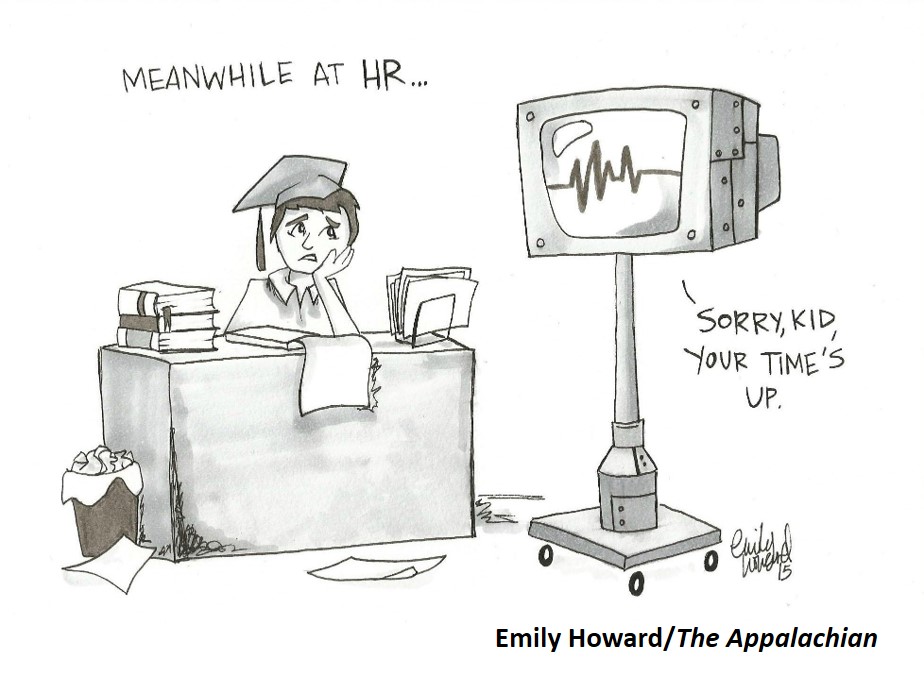

The most obvious is that the impact of AI on the economy will be enormous, probably more than we have even begun to really incorporate into our thinking. It’s already having real impacts, although in a somewhat stealth way. AI appears to be causing a slow-down in beginning level hiring in what have been considered attractive jobs. Today’s Chicago Tribune has two separate articles about AI taking tech jobs. Learning computer coding will become a whole lot less effective as career strategy, even as our reliance on computer deepens. It creates a serious problem for society if a material number of people who followed steps that were promised middle class (or better) jobs find it impossible to be employed. We have a real workforce problem, but it is rarely for people with more intermediate skill sets.

Another thing is AI’s voracious appetite for power. Current AI applications (excluding those in China, which surely add materially but for which data is not available) use as much electricity as the Netherlands. And this is expected to grow five-fold by 2028. It’s not obvious we have grid capacity for this increase, which, of course, will not be evenly spread around the world.

Then, of course there are well discussed threats of AI induced dystopia. I find most of them to be fairly abstract and, accordingly, feel distant. What does worry me more immediately is the ability of AI to be linked to authoritarian overreach. For instance, I can imagine it would give Texas law enforcement officials the ability to keep track of who is looking up information on out-of-state abortion providers. This is related to another concern: AI tools have broad enough accessibility that the capital requirements for application are relatively low. This will make it very hard to exercise effective oversight and very easy for rogue operators to commit malevolence. Indeed, we are already seeing that in creation of pornographic deep fakes for the internet.

In general, my concern about AI is less that it will trigger cosmic destruction, but rather it will amplify the various weakness and foibles of individuals and inflict them in ways never intended.

In short…

The purpose of today’s blog is not particularly to sound alarms about risks. The risks are certainly real, but there are already plenty of warnings. Rather, I am trying to make concrete the vertiginous feeling of being adrift in the space between the unprecedented positive possibilities and those risks. I can see what has been accomplished and appreciate the many wonderful potentials that open in front of us. But, dazzled as I am, I can only vaguely comprehend the science that allows some people to understand and manipulate the most intricate functions of molecular structure or the technology that allows all of the worlds’ knowledge to be available at the push of a button, including things not previously known. All of which contributes to making the risks equally vivid. Contemplating the difficulty of trying to reconcile in my own mind the possibilities and the risks—and maybe some way of mitigating the risk–gives me a bit of perspective on why some people would recoil at science in favor of simpler truths.

As a species, we like to think of ourselves as homo sapiens. Hopefully that works out. But what if it turns out that it would be more accurate to think of us as idiot savants.

****

Postscript: I very much recommend the mini-series, “Murder at the End of the World” streaming on Hulu. It is not without artistic flaws, but it does an excellent job of exploring what I am trying to get at in this post, the space between “Wow!” and “Oh crap!”