By Mike Koetting November 20, 2023

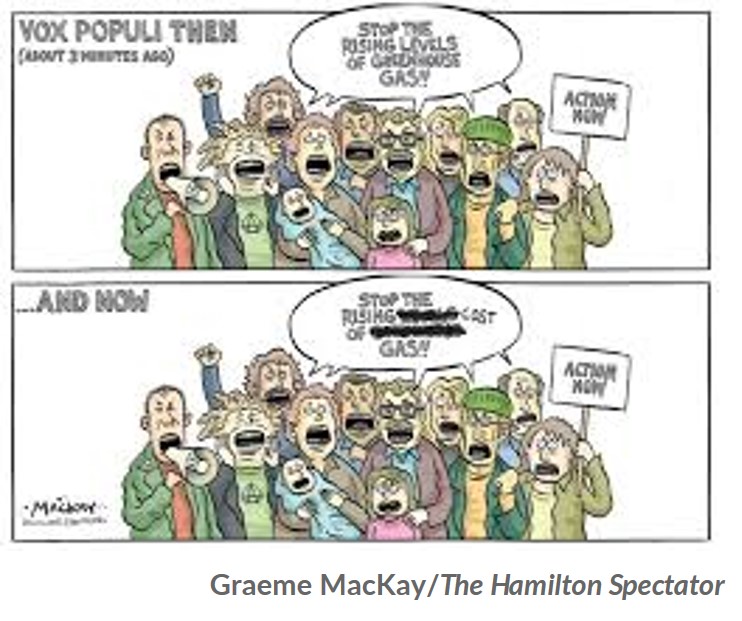

Two weeks ago, Lisa Cook, a governor of the Federal Reserve Board appointed by Biden, was asked why he was getting so little credit for the economic situation. She suggested that consumers judge the economy not by a slowing of inflation but by the prices they are still paying. People, she said, simply want gas prices back to where they were before the pandemic.

Don’t we all. I still flinch at what it costs to fill up our family car. Still, this comment not only explains why voters question Biden’s economic stewardship, but also puts a blazing spotlight on the long road ahead as economy and environmental realities collide.

Gas Prices in the Real World

Let’s consider two absolutely incontrovertible facts:

- The supply of oil is finite. Oil is presumably still being created, but it takes millennia. When it comes to oil we can use in our lives, Bugs Bunny put it best: “That’s all, folks.”

- The demand for oil increases—if for no other reason than population growth. The planet’s population has doubled since 1970 and increased by almost 700% since the dawn of the Oil Age. And they all want their share.

When it is teed up like this, it doesn’t require a Ph.D. in economics to see the inevitable trajectory.

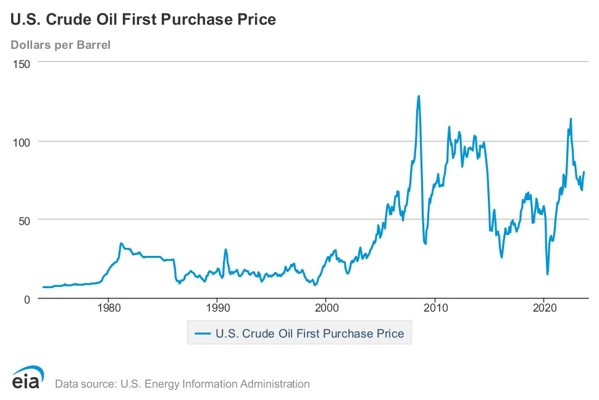

For better or worse, the issue typically presents in a more complicated way. In the short term, the price of oil is subject to all kinds of factors, including the predations of the oil companies, changes in the technology of oil production, wars, epidemics and other government policies. But even a modest step back shows that despite significant year-to-year variation, the longer-term trend is still shaped by the law of supply and demand.

Moreover, the problem is more than a simple extrapolation of population induced oil demand with a finite supply. All oil is not equal: the nature of oil extraction follows a predicable course of diminishing returns. The easiest to obtain oil is used first. Picture great “gushers” of oil early in the last century. Over time, successive extractions become more difficult and require more resources. From drilling and fracking for shale oil in Texas, through mining tar sands in Canada, to deepwater drilling in the Gulf of Mexico, all new sources of oil require more input per barrel than previous barrels. Again, the curve isn’t smooth—there will be new technology or some other factor that slows the rate of increase from time to time. But in even the medium term, costs are invariably headed up since oil companies will exhaust the less expensive to extract first.

Won’t Renewables Solve This?

Well…No, at least not for a long time. Ameliorate, sure. But we still have a big problem.

Here’s where it is really necessary to be hard-headed about reality, particularly difficult in an issue so drenched in hopes, fears and political injunctions. We must pursue renewables and talking about a “net zero” world helps generate enthusiasm for what we have to do. But simply setting a goal and being foggy about the steps along the way ultimately undercuts the goal.

Renewables will continue to grow, perhaps and hopefully at enormous rates. But it is not like we can flip a switch to go from the oil age to some other age, now or later There will be a long transition, and demand for oil will remain strong. Oil for transportation accounts for about two-thirds of our oil use. As electric vehicles become more common, that will decrease. But the transition to electric cars is not going as quickly as hoped, in part because of high cost of purchase. In the meantime, gas-powered cars and trucks are still being manufactured—in 2022 accounting for 86% of all purchases. With cars lasting, on average, more than 12 years, they are going to be around for a while. Jet planes are further from alternative fuels.

There is also the other one-third of oil demand. For many of these uses, we are just beginning to sort out what alternatives be might possible, let alone have them in place. Many of these other uses—for instance manufacturing of EVs and production of electricity and back-ups necessary to stabilize and smooth out fluctuations in renewable energy supply—will be required indefinitely.

There is no reason to expect the demand for oil to decrease significantly any time soon. Accordingly, waiting for sustainably lower gas prices is waiting for Godot. There is nothing Biden, or Trump or any other politician can do about that. They may be able to make a momentary difference, but the overall physics of oil supply and demand are inevitably going to push up gas prices.

This Is a Political Problem

Big time. A recent poll offers backing for Lisa Cook’s comments. By a wide margin, voters judge the state of the economy more by price increases/decreases than by number of jobs created or average wage increase. And gas prices are very high on the list of items in their yardstick. Gasoline is a large and essential part of many family budgets and fluctuations are as easily observed as driving past a gas station.

Thus, we have the spectacle of people believing Biden is mishandling the economy because gas prices aren’t coming down enough. Arguments that with more use of EVs gas prices wouldn’t be so important fall on deaf ears. The high prices of EVs make them seem like “rich people’s toys.”

Republicans go full on to exploit this situation. They continually blame Biden for high gas prices, they are unsupportive of EVs, they frustrate attempts at emission controls, and have even gone as far as to pass laws prohibiting financial institutions from steering away from investments in fossil fuel companies. Most of what they say is simply balderdash. For instance, U.S. oil production is near all-time highs and is on track to exceed previous highs. As Catherine Rampell ruefully notes in the Washington Post, Biden and other Democrats are hewing much more closely to the Republican pro-fossil-fuel agenda than either side would like to admit.

So, the situation is that we are sliding toward an uncertain future with both parties making politically expedient moves—resulting in faster speed to the time we run out of oil as an affordable commodity.

What we need now is as obvious as it is unlikely. We need politicians to square with the American people about the underlying realities. And we need an American people who are adult enough to accept those realities. Neither is likely as long as an honest reckoning with these facts is a political death wish.

I’m hard put to imagine how to break this cycle. It will take a number of real leaders, with strong media support, who are able to explain the realities we face. At one point this was not fantasy. Fifty years ago, both political parties supported the creation of the EPA, but that’s vanished in a toxic partisan fog. Over the years politicians and academics of all stripes have supported a Carbon Tax, which would put downward pressure on consumption, generate money for alternatives, and make it socially acceptable to recognize that energy will become more expensive. But now, although academic support remains exceptionally broad, it is politically taboo for politicians in both parties.

We are living in a golden age of energy consumption. It cannot last in its current form. Politicians and the media—science is already on board–will either help people accept this unpleasant fact or hurry us down the path to where the bottom drops out. And, note, this is true even without mentioning the inconvenient reality that continued use of oil is destroying the planet.

Final Observation

I can’t help but noticing that my last post was about why we need to make American governing institutions more democratic, while in this post I am positing that the attitude of voters to gas prices is irrational. Which leads to the possible thought that if the public is irrational on this issue, might it be equally irrational on other issues. These sorts of concerns keep me up nights.

Part of my rejoinder would be that it is hard to help people be more rational when there are so many vested interests blurring the issues. Some of that might be reduced with more democratic institutions. But more fundamentally, this underlines the sustaining need for leaders who are courageous, eloquent, and in accord with reality. I get that when it comes to talking about the future, it is not always easy to figure out what “reality” will be. But with oil futures, we have an unusually high degree of confidence about the challenges of the road ahead. If our leaders continue to hide from them, democracy will not save us. It will get very cold in winter.