By Mike Koetting September 12, 2023

Today’s post is not about China. Well, maybe sort of. But it’s really about what we can learn from the recent turn in the Chinese economy.

For the past few weeks there has been a tidal wave of coverage about the slowdown in the Chinese economy. From Al Jazeera to the Wall Street Journal, everyone has had a prominent story about how the Chinese economy is sagging. I don’t know enough about either China or economics to assess the situation in detail, but the biggest question in my mind is “Why would anyone be surprised at this?”

There are a host of specific partial answers to that question, but most of them are covered by an observation that society doesn’t typically anticipate the future very well. No surprise. As the old witticism goes, “It’s hard to make predictions, especially about the future.” Even if you’re pretty sure you know what is going to happen, you might not know when, or how much, or what other events will also affect the consequences. And sometimes the anticipated event doesn’t even happen. So the easiest thing to do is assume that things will continue more or less along the current path. This is particularly tempting if it looks like the future is going to involve major changes in what the “powers that be” had planned.

Back to China

As I understand the Chinese economic problem, there are a number of issues—a bubble produced by speculative over-building, clumsy handling of Covid, other economies striving to be more independent of China, and political meddling in the economy. But the more fundamental problem is demography. Last year, the country’s population fell for the first time since the Great Famine in 1961. This epic change in direction had not been expected until 2029 or later. From here on, China’s demographic decline will accelerate: The United Nations projects that the country’s head count will plummet from today’s 1.4 billion to below 800 million by century’s end. And as the population shrinks, the ratio of workers to older people will increase until there is a new population stabilization.

What’s most noteworthy to me about the coming demographic problems is that for years everyone has known they were coming. Probably some people figured the downturn wouldn’t be so soon. Even fairly recently official Chinese government projected population decreases wouldn’t start until 2033. But the general shape of things to come couldn’t have been a surprise to anyone with access to the Internet.

The obviousness of this issue notwithstanding, up until recently much of the world was fretting about the coming Chinese economic takeover. One can only assume they were extrapolating from graphs showing remarkable economic growth over the last several decades. To be sure, the Chinese economic gains have been impressive. They have transformed China. And, it is my guess, China will shake some of the specifics now dragging at it and will continue to experience significant economic growth for at least the near future. China is and will be an important world power for some time. There is nothing in their current economic woes that suggests the United States does not have a pressing need to come to continuing accommodations. Still, the future of the Chinese economy will inevitably be marked by a population collapse, the likes of which haven’t been seen since the plagues and famines of the late medieval period. We should expect continued difficulties in that society.

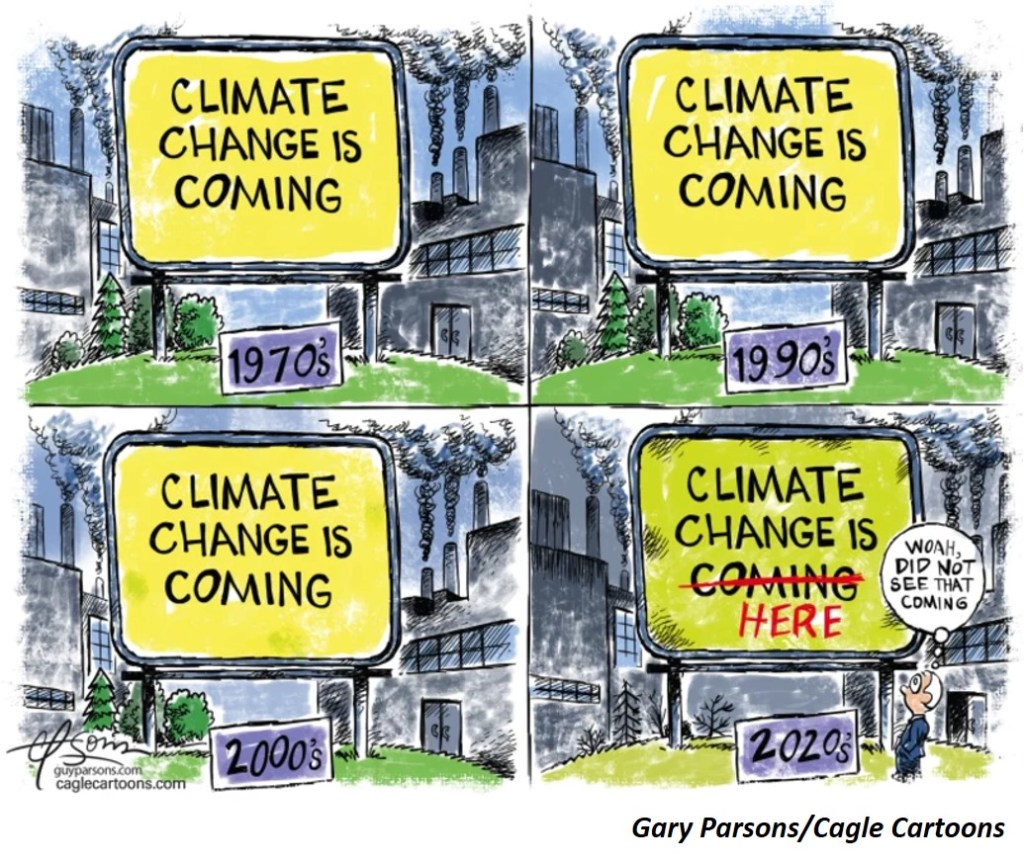

This demographic reality has been glaringly obvious for some time now. Each year the trend continued made the conclusion more and more likely, at some point reaching inevitability, even if the moment of reckoning was some years away. Nevertheless, we treat the economic consequences as something of a surprise because we aren’t good at responding to predictions about the future.

Lessons

In 1972 a group of MIT scientists, funded by the Club of Rome, created a computer model of the world’s resources, consumption and trends. Their report’s title was The Limits to Growth and predicted huge environmental problems in the middle of our current century in the absence of specific action to avoid these problems. I stumbled on the book at the time and it sure caught my attention. Beyond any of the specifics, what stayed with me was the observation that when things are accelerating, the moment of impact will appear farther away until the last few moments. It is the less colorful expression of Hemmingway’s observation that when you go broke, it is very gradual, then all at once.

In the fifty years since those projections, there has been a fair amount of back and forth as to how accurate their predications were. At the rough eyeball level, it seems that their predictions so far have been pretty good. But, and this is a huge but, they are just getting to the really hard parts for their predictions—the inflection points. Up until now, things were generally following the same trends they were on. The question is when do those big changes happen—or will they happen at all? So, a grain of salt is still warranted.

Which does not mean we can ignore these predictions.

In the first place, the consequences they predict with these underlying trends are really big. And unpleasant. By no means does that mean the predictions are right. But it does suggest this is something not to be taken lightly. A huge body of research since then seems to support the notion that these estimates are well within the bounds of what should be necessary to trigger serious concern, in fact, are currently very likely. Cutting off environmental standards reporting—something many Republicans seem eager to do—will not change the science as it emerges.

Second, waiting till the inflection point is upon us—that is, when it’s all about to hit the fan—is dangerous and expensive. If we had moderated trends as they suggested in 1972, we would be in a very different place. It’s possible, when everything was considered, we wouldn’t have liked those consequences any better than our current situation. We can’t know. But we do know that we had opportunities for a softer environmental landing and chose not to pursue that course. It remains to be seen how bad, or how good, those choices were. But make no mistake: there were alternative courses that the world did not pursue.

Third, given the magnitude of the consequences, and given that there is more than enough research to support the idea that these outcomes are all too possible—wouldn’t it be sensible to take steps now to do whatever we can to moderate possible problems in the future?

The last question is largely, but not entirely, rhetorical. Whatever steps might be taken will come with costs—not just actual out-of-pocket costs, but lost opportunities. Those could be steep. So when considering actions to protect the environment, we need to be taking into account the full costs entailed. The question then becomes how do we allocate our resources to get the best possible balance in avoiding problems predicted for the future with the reality that the predictions will be imprecise and possibly just plain wrong?

Here We Are

China is pretty well locked into its short and medium term maternity trends. Once put in motion, demographic trends have a long tail. At some point those trends became more or less inevitable for protracted periods. For China that ship left a while ago. It is just that now the real impacts are now being felt in their economy.

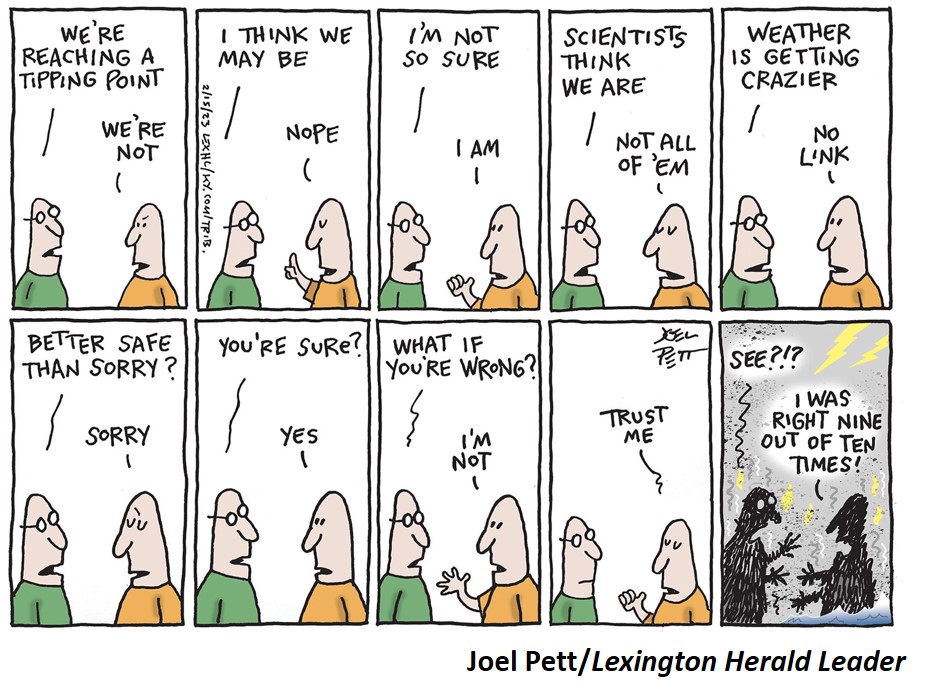

Likewise, we have been amply warned about environmental constraints. The problem is that people are pretty hard-wired to minimize problems in the future. That may be culturally adaptive; risk is an element of any innovation. The question is how and when do we decide that the possibilities of threat outweigh the difficulties of change, which includes the opposition of interests more vested in the current situation than a more generalized sense of good. It is certainly wrong to yell “Fire” in a crowded movie theatre if there is no fire. But is it equally wrong to not yell “Fire” if we believe there is one? At what point does the chaos that would cause outweigh the dangers of staying silent?

Chinese demography and world environmental concerns are different on any number of dimensions. But just as no one should be surprised that the Chinese economy is struggling because its population is falling, no one should be surprised that we have experienced multiple environmental catastrophes this summer with full anticipation of more to come.

I don’t know the point when we hit some irrevocable climate “tipping point”—indeed, whether we will actually do it. But I do know that at least until now, there has been no willingness to believe the many predictions that crucial “tipping points” may not be that far away, let alone a willingness to make drastic changes. We’ll see if that’s a good bet. But, like the Chinese situation, if we do get there, we’ll be in a hell of a mess that will be hard to change quickly. Or virtually impossible.