By Mike Koetting September 1, 2023

As I am restarting after a break, I thought it might be a good time to make a really high-level review of the three things I identified as core issues for the country and the world when I started the blog, six years ago:

- Dealing with vast inequity of resources among people

- Radically revising our relationship with the environment

- Rethinking the nature of work

It is my impression these are still the critical issues. Moreover, it also seems there is a fourth major question that didn’t seem as omnipresent six years ago.

- Assuring the future of democracy

How’s the world been doing on these issues?

Quick Scorecard

Given these are profound questions that get at the very nature of societies around the world, it would be foolish to put too much emphasis on a period of time as short as six years. On the other hand, it is a long enough period to determine in what direction the wind is blowing.

The state of resource equity—either globally or in the US—is for books, not a few sentences. But a quick look at World Bank data shows some poor countries (China and India, in particular) have had substantial growth since I started the blog. But the differences with developed countries are still staggering, and changing inequities within those countries may raise different issues. Heading in a different direction, income in Sub-Saharan Africa has actually fallen and poor countries in Latin and Central America have experienced virtually no growth. If we think about inequality in terms of relative carbon contributions, every person in the United States contributes more carbon than hundreds of people in Bangladesh.

In the United States, income has continued to become more inequal. For instance, between 2015 and 2022, share of household income to the top 5% has increased from 22.1% to 23.5%; share of the bottom sixty percent decreased from 25.6% to 24.8%. Even those with income between the sixtieth and eightieth percentiles slipped from 23.2% to 22.6% of all income. In short, 80% of families lost ground compared to the top 20%. Small wonder so many people feel stressed about the economy.

Black-White income differentials continue to ebb and flow, but the wealth gap remains huge and is seemingly impervious to simple fixes.

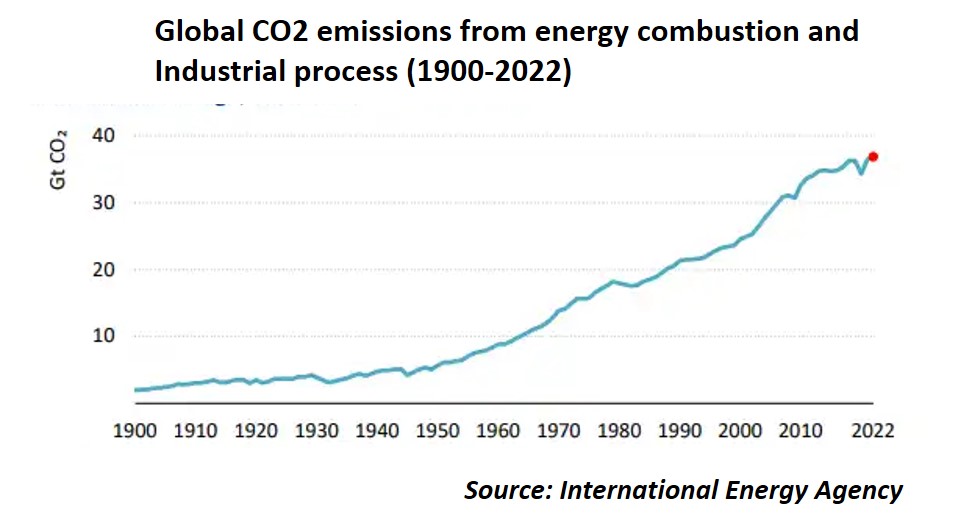

Our relationship with the environment has been endlessly described this summer. But in the back and forth about various catastrophes and specific policies, there is insufficient notice that the world’s use of fossil fuels continues to rise as if nothing unusual were happening. 2022 had the highest global CO2 emissions on record. We had just a small reduction during the early days of the Covid pandemic—which as you may recall brought the global economy to its knees—but it has bounced back pretty much on the same path it’s been on since 1900. Our response to environmental threats doesn’t seem commensurate with the size and complexity of the problem. This is old news. But still not responded to. I don’t believe at this point there is a feasible model for addressing the intertwined causes of the environmental crisis at a reality scale. The political world is divided between those who use the lack of a coherent plan for the future as an excuse to continue our suicidal course and those who don’t want to acknowledge the issue for fear it would jeopardize what immediate gains might be possible.

I don’t think there has been any material progress on rethinking the nature of work in the last six years. The startling, even though well anticipated, advances in artificial intelligence have made the issue more salient. The problem remains that automation is eroding the connection between work and social well being that has obtained since the dawn of humanity. To be sure, AI raises other profound concerns—and offers many potential advantages—but for sure it increases the probability of even larger scale reductions in the number of workers necessary to support humankind. How does society function if a significant number of people are no longer contributing to the economy? Do the people who retain economic relevance support those made redundant? And, even if arrangements are made to offer some level of support, can we address people’s sense of self-worth as well as their physical needs? The examples we have—economically abandoned inner cities and rural communities—are not encouraging.

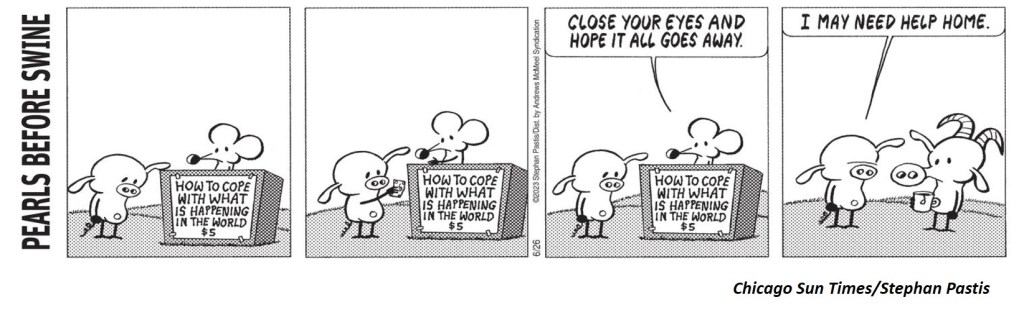

The potential consequences of these changes are so earthshaking, they only get sidewise attention. Like environmental issues, there is no model for thinking about changes on this scale. The distance from current mental models and structures is so large as to strip the gears of the political thought process. Also like environmental issues, the approach of this problem has been seen from a long way off. Since addressing it was so difficult and the time of reckoning seemed far away—and likely to affect “others” first–we frittered away time to prepare for the coming firestorm. While I understand the psychological mechanisms, I don’t understand why there isn’t a stronger rational thread in society for identifying dangers and taking steps to mitigate them before they threaten to overwhelm us.

Like the other issues, the threats to democracy have been well described. In America, the Trumplicans have moved to a fairly open embrace of Victor Orban-style soft fascism and far right parties are gaining traction in even unlikely places like Sweden and Demark. Undemocratic institutions have many downsides, but of particular relevance to this discussion is that autocrats, from Trump to Xi Jinping, tend to put their own survival above any other value. This means they are less likely to embrace projects based on global well being. But a striking feature of all three previous issues is that they cannot be addressed without some degree of global cooperation. If “Making America Great Again” comes at the expense of other nations—intentionally or incidentally—it places the survival of the species at greater risk.

All Together Now

As I did when I first reviewed these issues, I hasten to note that while each of these is a somewhat separate issue, all four of these issues are inescapably connected. We can’t simply “grow” our way to more equal resources because the environment constrains how fast—or even how much—economies can grow. These constraints pose significant threats to even the most robust of economies. Nevertheless, environmental constraints are leading to “greenlash,” typically embraced as part of right-wing populist appeal to dump democracy. It seems almost axiomatic that part of the appeal of Trump (and others of his ilk) is that they speak to the worth of people who have been left behind by the evolving economy or can see the writing on the wall. This can only get worse as AI steams along.

Unfortunately, people aren’t well wired to make these connections. A recent poll by Pew of Americans’ top policy concerns placed “the economy” in first place and protecting the environment in 14thplace. I do understand that “the economy” is a totally protean concept not only from person to person but within people over even short time spans. I would submit that for many people “the economy” is really shorthand for either “I am really having trouble making it economically” or “I am really afraid I might easily slip into this situation”. Fair enough. I understand why that is the number one concern. It is consistent with the fact that 80% of the families are losing share of income. But what’s missing is the next step—understanding why they are having difficulties and where are the major threat points and how these issues are connected. There is no obvious answer for this. The major political parties don’t help because, understandably, they tailor their messages to meet concerns as perceived by the voters, rather than helping the voters understand the true nature of the situation.

A platform steeped in reality would include the following elements:

- We’re in really deep trouble and, in truth, we don’t know how to get out of it. No one group has answers that are sufficient.

- We need to put full attention into developing models that do a better job of meeting the spectrum of constraints—rather than pitting them against each other. Then we’ll have to execute.

- To do this we will almost certainly have to tax the daylights out of rich people and develop working partnerships with countries around the world.

And if that isn’t “reality” enough, such a platform could add that it’s possible that most people in developed countries could experience some decline in standard of living and there is some chance a huge number of people will die in the process.

It’s not hard to see why we haven’t made much progress against the large issues I have been writing about in my blog.

Conclusion

The evidence seems to suggest things are getting worse in the last six years, despite my many helpful suggestions. Of course, I plan to keep writing, in part because I hope it will provide some modest exculpation when the grandkids realize how lousy a job our generation has done in stewarding their future. I suspect, however, there will be at least some raised eyebrows about the disconnects between my words and my lack of enthusiasm for reducing my own lifestyle.