By Mike Koetting September 19, 2021

Among other things, the ongoing controversy over the public health response to Covid serves as a kind of political x-ray machine illuminating the gap between our mental image of how our government works and how it actually works, something that can get lost in the trivia of day-to-day politics.

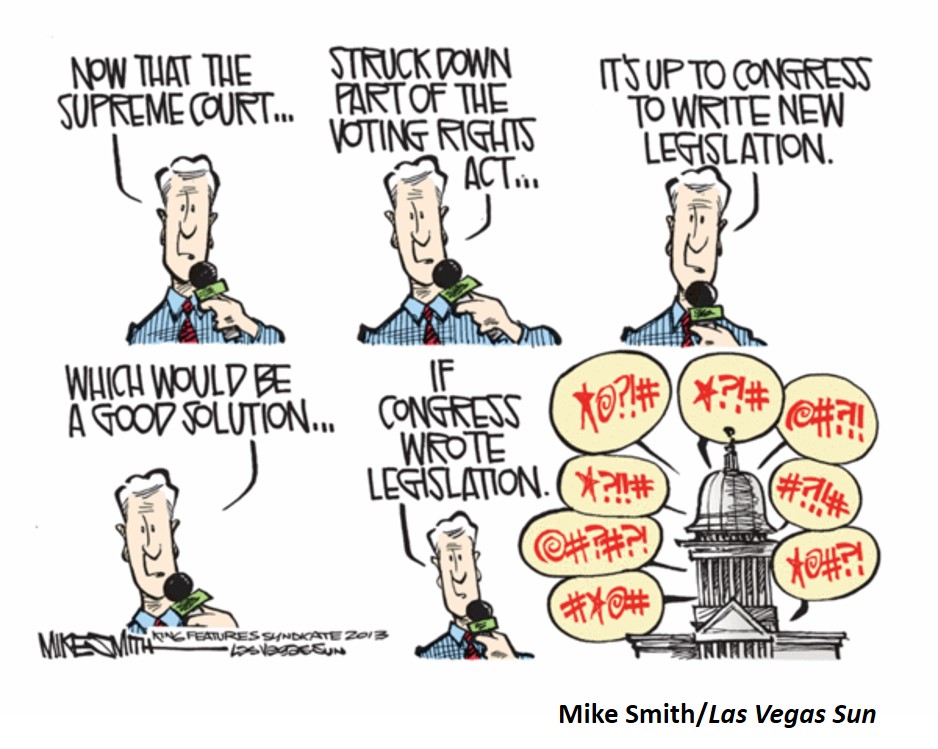

Congress Is Hopelessly Broken

In civics we teach that in America the elected representatives address serious problems through law. While at first onset, responding to Covid is something that would require emergency Executive action, this issue has been roiling for 18 months now. Any textbook description of our democracy would suggest some of these issues should be taken up by Congress and resolved through the passage of a law that reflected democratic debate and resolution. The Executive branch would then be charged with implementing the resulting law.

Of course, anyone who has paid the least bit of attention to recent American politics would giggle at this idea. I have never heard anyone even suggest this as an alternative route for addressing how forceful the government should be in addressing the pandemic. The country takes for granted that there is no amount of scientific evidence that would compel Republicans to seriously consider public health mandates and the structure of our system is such that any substantial minority can bring the system to a halt.

Whether this is an indictment of the current status of the Republican party, the structure of our government or both is not relevant to this discussion. The point here is that no one can even imagine Congress usefully addressing this issue.

This is not an isolated case. Despite the fact that Congress passed large COVID relief packages—and may actually pass one or two large-ish infrastructure bills—the Congressional record for this century accomplishes little beyond firmly establishing its inability to address the fundamental problems of the country. Whether it is immigration, environmental issues or inequality, Congress is at best a debating society and, probably more accurately, a sink-pool for various rhetorical themes. Ten years ago, Ornstein and Mann titled their book on Congress It’s Even Worse Than It Looks. The intervening ten years have only made it look worse. A recent Pew Survey found that a substantial majority of Americans think Congress is broken—73% think citizens, not Congress, should decide on laws, a horrifying prospect.

The implications of this lack of confidence in Congress are far-reaching. The country spends billions of dollars on Congressional campaigns to elect a Congress that will consume a very substantial percentage of the media time devoted to policy discussions for an institution that is largely derided in the rest of the country and has become functionally irrelevant to actually solving problems. Both sides hope for little more than to block the other side from getting what it wants.

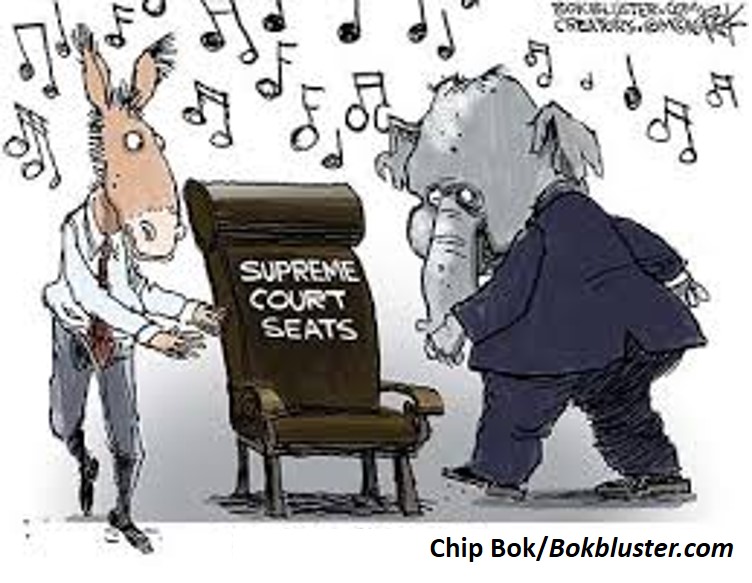

Courts Are Worrisome

The absence of Congressional ability to do much of anything, splits up power between the President and the Courts, in a funny kind of way. Since Congress no longer actually does anything about hard issues, if anything is going to happen, it is up to the President to issue some kind of Executive Order to mandate his (or, maybe even someday, her) idea of what needs to be done. Then the courts get to decide whether or not to let it stand. Since there is no specific law on which the courts can base their decision, they have a lot of leeway.

Although this is neither the original design nor the historical practice, so far it has not been disastrous. The courts allowed many of Obama’s Executive Orders to stand and stopped some of the worst of Donald Trump’s. But Executive Orders are no substitute for legislation.

Nor is there any guarantee going forward. Republicans understood the direction this was moving before Democrats were able to respond effectively and stacked the courts with ideologues who had life-time appointments. Surely at this point Democrats would do exactly the same thing if they could; once the trend started, the other party has to respond similarly as a matter of self-defense. The functional outcome is that the courts will be reflecting the preferences of whichever party (or fraction of a party) managed to cobble together enough votes at a time when there were court openings. Any changes in popular will or circumstances since then may or may not be relevant.

The case of a vaccine mandate illustrates the difficulty in technicolor.

The standing law on this matter is pretty clear. Dating back to the 1905 in Jacobson v. Massachusetts, the Supreme Court decided that jurisdictions do have the right to require people to get vaccinated. Justice Harlan, at the time, wrote:

Of paramount necessity, a community has the right to protect itself against an epidemic of disease which threatens the safety of its members.

That position has been challenged and rechallenged in the years since and in all cases the ability to impose mandates was upheld.

Nevertheless, I am not sure that the current Supreme Court would uphold a broad vaccine mandate. I think they would. But I am not particularly confident. Others share my uncertainty. The underlying nature of the courts has taken some serious hits in the era of Mitch McConnell. While the idea of checks and balances among branches makes sense, when it’s taken to the extreme that has happened over the last several years, one has to wonder whether the practice has overshot the original rationale.

Not Much Guidance for Executive Branch

This leaves the President in a difficult situation. He can’t rely on Congress and he can’t be certain the courts will pay attention to previous rulings, to popular sentiment, or indeed anything beyond their preferences. He also faces a situation where there is little agreement on what constitutes the safety of the community that Justice Harlan said was paramount. More than 660,000 Americans have already died of Covid and another 100,000 may die by December. Most of the deaths since early summer have been among the unvaccinated. But even that is not enough to create a political consensus.

If the unvaccinated and others ignoring public health recommendations did damage only to themselves, the grounds for a mandate might be murkier. Unfortunately, it is indisputable that these folks contribute significantly to the continuing spread of the disease to the vaccinated and pose the risk of generating mutations that may do even more damage. It is also the case that caring for the unvaccinated runs up healthcare costs for all of us and, in many communities, is flooding medical facilities to the extent others are in danger. Over 95% of Covid hospitalization since June are for unvaccinated people with an estimated preventable cost approaching $6B—through August alone.

This is aside from any benefit that might accrue as a result of saving people from themselves, although I concede it’s a bit tricky to figure out what the correct balance is when it comes to saving people from themselves. As a society, we do a fair amount of trying to save people from themselves and the results are mixed. Still, this seems like a relatively clear case.

Despite all that, a material number of people in the country seem to believe that any infringement on their ability to do whatever they want is a violation of America’s promise of individual freedom. Relatedly, segments of the population have completely rejected expert opinion as a basis for policy, which further undermines the ability to generate consensus.

With few universally accepted guidelines for making policy choices, it is inevitable that any decision the President makes on a major issue is going to be hotly disputed by a big enough fraction of the population to make actually implementing an Executive Order extremely difficult. It is particularly problematic when those dissenters are disproportionately concentrated in a few states which gives those Governors incentives to use the power of their offices to actively obstruct any Executive Orders.

Common Factor

All these aberrations from the understood machinery of our government have a common problem—the loss of willingness to put a common notion of democracy over one’s individual opinion.

To a certain extent all democracies require this kind of compromise and all are facing increased challenges in this regard. But, as Max Boot points out in the Washington Post, other democracies have been able to do a better job of getting their populations vaccinated—the US is behind every other Group of Seven country’s vaccination rate. He suggests this is not the only important issue where the US gets tangled in its own shoelaces and argues that the problem is the United States has developed an “uniquely dysfunctional political system.”

Whether this system can be fixed is probably an even more important question than vaccine mandates.

People run for office for at least two very different reasons: to work for the common good or to promote a special interest. Until we have serious campaign finance reform to reduce the influence of special interests and force politicians to go back to the people for their mandates, we will continue to be plagued by elected officials pursuing goals other than the common good.

Getting rid of gerrymandering (as my grammar school text books once assured me we already HAD done) is essential to reforming Congress. There are states like Washington that do it well. Such bipartisan commissions should be required in all states.

LikeLike

Michael – Wait just one minute. In passing, you called the $4 TRILLION plus cost of the infrastructure bills as just “large-ish.” I am no tea-partier, but I would call it “mind-boggling.” This is all money the government does not actually have, and so if the bills are passed the cost must be added to our record setting national debt of more than $27 trillion. I love what Biden has proposed in terms of its possible impact on society, but where is the line where politicians should say: You know what? We just can’t afford this. – Jim

LikeLike

There probably is such a point. But “afford”–particularly at the level of countries–it is a really tricky matter. It depends on what is being purchased, how revenues are determined, and a variety of other factors. Could we afford the, much more expensive, wars in Iraq and Afghanistan? The $1.7 trillion tax cut for the rich? The huge bailout of banks in 2008 and 2020, the latter of which no one even noticed? Those questions don’t explicitly answer the question of what we can “afford”. But they do make it clear our lens are seriously fogged when it comes to thinking about what government can spend money on without causing damage.

LikeLike