By Mike Koetting July 16, 2018

Needless to say, I’m not expert on trade policy. But with the issue at the front of every media report, it is hard to avoid. And equally hard to determine what one’s own position should be. Both political parties find adherents of every view within their party. So even with a souvenir program, it’s pretty hard to guess where someone is going to come down on these issues—let alone whether that position makes sense.

Not knowing much, it seems to me that the logical place to start thinking about trade policy is to ask what a country wants from its trade policy. But even with a simple answer to that question, to help the country obtain maximum benefit from its trade, it doesn’t take long to throw to up one’s hands at the complexity of the thing. It’s more than the obvious fact that in a $20 trillion economy there are millions of moving parts. The whole conceptual base is swampy.

For openers, what does it mean to make “the country better off”? While there are national trade accounts, it by no means follows that the country is better off by showing a positive balance. For instance, If the impact of trade with China lowers consumer costs below what they would have been in the absence of cheap China imports by an amount greater than the trade deficit, how bad is the deficit? And what happens if a trade war goes, so to speak, nuclear. Paul Krugman suggests the consequences will be very disruptive to our economy and there would be little likelihood that the net benefits will offset the losses.

Then there is the question of distribution of benefits from trade. For instance, if 95% of the benefits went to one million people, would the country really be better off? That is not an entirely rhetorical question since the bulk of the benefits of trade policy in America for the last 40 years seems to have been realized by a small group of owners and investors.

Third, it is necessary to choose a time-frame over which to consider benefits. Under conventional economic theory, if things are “out of whack” over time, relative changes in value of corresponding currency is hypothesized to bring things back into balance. Although it rarely works that way in real life, it is generally the case that there will be some adjustments in economies as trade balances fluctuate. So there needs be consideration of longer term implications. Does our trade policy make other countries more or less willing to do business with us over time? If countries feel we are bullying them, or otherwise threatening their long term welfare, we may still reap short term advantages. But over time, the costs of maintaining those advantages will surely increase, quite possibly to more than the short term gain.

All of this makes it clear that the issue of settling on a trade policy isn’t going to happen by people demanding “Free trade,” or deriding any constraint on trade as “Protectionism” or any other one size fits all approach. No country in the developed world has ever had completely “free trade”. The very essence of establishing a trade policy is to establish rules of the road and those inevitably give a green light to some practices and a stop light for others.

The good news in this regard is that most of the media has begun to acknowledge that sensible discussion of the trade issue is going to require much more detailed analysis of the issues. The bad news is that the electorate isn’t there, and, of course, if the electorate isn’t, one shouldn’t expect too much from politicians. While there may be a certain grim satisfaction in finding the Republican party corporate interests at war with the Trump base, the Democrats aren’t doing that much better. One wing of the party is intent on getting rid of all trade agreements, while another wing—which has historically been enthusiastic supporters of “free trade”—finds itself unsure of its footing on this issue and is primarily content to call attention to the Republicans’ problems.

About the only thing for which there is a broad consensus is that our president doesn’t seem to have any particular trade strategy and is lashing out (or capitulating) to meet short-term, largely emotional needs. His base supports him because it feels good…not the first time people have sacrificed real money for ephemeral pleasures. It is also important to keep in mind that trade policy is not the biggest factor impacting American workers. Automation and other forms of manufacturing efficiency have had a bigger impact. But trade policy has become a convenient emotional release point.

Before turning to the question of what would a sensible policy look like, let me make one observation: there is no solution in which some Americans don’t, one way or the other, pay more. There is a straightforward reason for this: because we have been supplementing our life style on the backs of lesser developed countries.

We need to be clear here. The third world does not necessarily see this as a bad deal. Or at least hasn’t historically. The evidence is fairly clear that on balance the relatively free trade of the past fifty years has improved standards of living in those countries with whom we trade. The improvements in life conditions have not typically been evenly distributed, but have nevertheless been widespread. (As living standards improved, generally speaking, inequality increased. The appropriateness of any particular balance is something that each country needs to work out for itself.)

But whether or not those countries have liked the terms of the deals, the deals were obviously exploiting differences between wages and working conditions in America and wages and working conditions elsewhere. If owners didn’t think they could make sufficient profits with American workers in unionized jobs with safe working conditions, moving production to Bangladesh with lower wages and bad working conditions allowed them to charge American consumers less and still hit their profit-target. Increasing tariffs is one way to reduce the premium for producing in less developed countries. And, accordingly, it may increase American jobs. But someone has to pay for that.

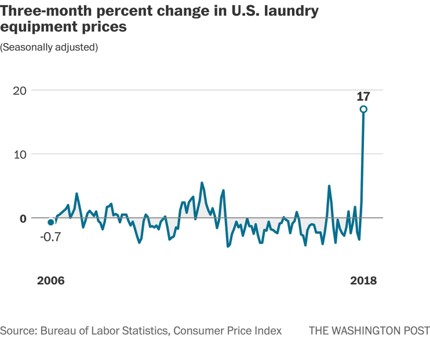

An interesting Washington Post article illustrates clearly how this happens. In January, Trump—at the urging of Whirlpool, America’s last remaining large manufacturer of washing-machines, raised tariffs on imported washing-machines. Two large Korean companies (Samsung and LG, who between them now control more than 50% of the US market) announced plans to build US plants. Good. More American jobs. But, as shown in the below graph, the cost of washing-machines to consumers shot up by 17% over three months.

Now, three months isn’t a long time so maybe there will be some subsequent adjustments. But as much as Mr. Trump is annoyed by it, the laws of physics apply. If you move from less expensive production sites to more expensive sites, costs go up. And unless owners reduce profits to compensate, prices will follow. In at least this case, it is very likely higher consumer prices will aggregate to more than the benefit of the jobs created. And that’s before the full impact of steel tariffs kick-in—or the explicit threat of tariffs on American washing-machines from Europe and Canada. And then there is the cost of tax rebates, subsidies and infrastructure improvements that state and local governments have offered to attract these new plants.

I point this out not to gloat that Trump doesn’t know what he’s doing. There is no evidence he does. But that’s not the point here. The point is that actions produce reactions. We can’t begin to have sensible discussions about trade policy unless we all start off with the understanding that the issue is neither trying to get to a zero trade deficit nor to simply maximize American jobs. We will need to evaluate trade considerations in the context of their impact on a broader set of considerations, especially domestic considerations. The results are likely to be not only complicated but to some degree painful.

But they may be overdue.

Regarding trade balances, I believe there are also ethical considerations. We have ethical obligations to all humans, not just Americans. If a particular country produces cheaper items but under especially bad working conditions, I believe we are ethically required to reduce trade with them, and tell the country’s leadership our trade would increase if working conditions there improved.

In the long run, we aren’t graded by God, the Constitution, or the economy on the basis of our trade balance. Rather, it’s by how we treat *all* other people.

LikeLike

Do I have it right that “free trade” means that only market forces restrain trade and “trade policy” means putting a thumb (tariffs) on the scale for some but not all imports? If our preference was not to do business with countries that had lousy human rights or worker rights we would adopt a “trade policy” that burdened their cheap products with tariffs. Correct? Similarly if we chose to affirmatively protect our automobile (or airplane) manufacturing industry we would adopt a “trade policy” that burdened car and plane imports with tariffs, making our products more competitive. As a political matter does the president have the power to change and manage “trade policy”?

LikeLike

That’s the idea…except that trade policy probably goes beyond tariffs. As we are apparently finding out with China, given the complexity of modern trade, a country has a number of other levers. (E.g. how many inspections are necessary for a product to enter a country–and how soon can they happen.) The division of authority between the president and Congress is as a practical matter something that needs continuous negotiation. The president can do whatever he (or, someday, she) wants as long as Congress or the courts don’t get in the way. Conversely, Congress can rein in the president to a large degree–if they have the spine to do it. Absent Congress strongly setting a different agenda, the president will have his way.

LikeLike