By Mike Koetting May 31, 2017

Last week’s post described two fundamental problems with the Republicans’ concepts around the health enterprise. Taking on these misconceptions directly, I believe, leads to two equally fundamental steps we must take if we are ever going to get this even close to right.

*****

Republicans make two fundamental mistakes about health care—they think it can be addressed by conventional market strategies, and they think poor health is at least partially a moral failing. Standing each of these on its head, however, outlines two important ideas for fixing our health care system.

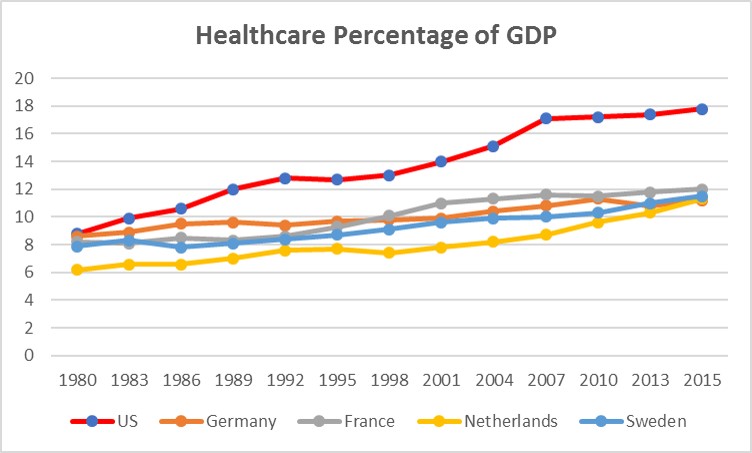

We need to start with the understanding that our current system is utterly unsustainable. It is, by a huge margin, the most expensive in the world. Worse yet, it continues to grow faster than the overall economy, choking out other critical uses of public funds. It does produce good results, in some cases very good results. But it also has some gaping holes and by no objective outcomes assessment is it the best in the world. Its quality is indisputably not commensurate with the price differential and it is full of discrimination. It is no great bargain.

Source: OCED, 2015 via post by Commonwealth Fund

Source: OCED, 2015 via post by Commonwealth Fund

Let’s Make Health Care a Right

While this may sound axiomatic to most of you, it’s anything but. As a society, America has resisted the idea of health care as a right. America is only belatedly, and through a twisted evolution, backing into acceptance of this idea. Unfortunately, much of the infrastructure of our health care system was built on resisting the concept. Maintenance of many of these measures serves little purpose other than to avoid admitting that we have reached a virtual acceptance of healthcare as a right. We would be better off if we focused our attention on making the actual provision of health care as efficient as possible rather than trying to create increasingly contorted “market systems” that don’t fit circumstances as they have become.

If we recognized that everyone is entitled to a predictable level of health care in a much less contingent nature, we could plan for that. This will be good for individuals, providers and insurers. In the absence of that, there are insufficient, often conflicting, incentives to thinking about longer-term health costs. Or to thinking about the host of second order impacts on related systems, like distortions in the labor market.

As it stands, huge amounts of health care dollars disappear into the cracks between coverage, the stutter-steps of entering and leaving markets every year, and the need to constantly re-invent all relationships with healthcare providers. This is at its worse with Medicaid, which now covers about 20% of all individuals in the country, including many of the most vulnerable. In our eager quest to make sure only those who are sufficiently poor receive Medicaid, we yo-yo a large portion of this population on and off Medicaid making the concept of continuity of care a joke. Some of the additional costs get picked up by Medicaid later because expensive treatment is needed, some are eaten by providers (later passed on to others), and some just result in sicker Medicaid clients. It is impossible to see the real benefit here. If we want to reduce health care costs, we need to focus on the health care itself instead of spending so much effort deciding who’s eligible for what.

I would point out this is not the same as simply saying “single payor”. And I’m not suggesting insurance companies are going to go away or this is going to make all health care available to everyone all the time. All I am suggesting here is that we start out planning that every citizen will always be covered by a predictable level of health care and plan our systems—including the actual systems of care provision—accordingly.

Frankly, I have no idea how the Republicans can get themselves to accept this. But they should. Making health care a right is not just a moral issue. It is, paradoxically, one key to controlling our runaway costs.

We Do Need to Pay Attention to Individual Behavior

Individual behaviors are really—really—important factors in health and disease. We need to address the role they play. The Republicans have made this harder with their tendency to treat “individual behavior” as a moral marker. Republicans can apparently get away with seeming to blame the victim; Democrats can’t. The discussion is further muddied by the plausible suspicion that “individual behavior” is code for “African-Americans and immigrants”, even though a boat-load of recent research is showing that much of the worse damage is being inflicted on poor and working class whites. And if that isn’t enough, lobbying groups with huge economic interests who support protecting health benefits generally—pharma, hospitals, device manufacturers, specialty physicians—keep the focus elsewhere. As a consequence of these various strains, there is insufficient political oomph behind working notions of how to actually change individual behavior.

While there is a lot we don’t know about how to get people to behave in healthier ways, there are many things we do know. We need to start with those.

- We know that it is possible to change individual behavior. It does take effort, but, for instance, we have seen very significant changes in smoking patterns. Likewise, motor vehicle fatalities–at least until a new individual perversion, driving while texting, hit the streets. The work is never done.

- We need to recognize that changing individual behavior does not happen overnight, another reason Republican rhetoric about making people responsible for their health outcomes is so cynical. There will be little quick “return” from working on these behaviors and reimbursement structures need to take this into account. Incentives for providers, including HMOs, that reward behaviors in a one-year time frame are not likely to be effective.

- The providers who will be most important in these efforts are not pharma, hospitals, device manufacturers or specialty physicians. There may be roles for all of them in this work, but they will be secondary and supporting roles. The most important work will be done by primary care physicians who have enough time to listen and psychologists, generously assisted by nurses, social workers, mental health counselors, dieticians, and others.

- There is plausible and growing evidence that many of these efforts are most effective (and, actually, less expensive) in community settings. Another paradox: changing individual behavior is often a group activity. At present, we don’t have good ways for incorporating these critical supports into the broader health system in a way that recognizes their centrality as opposed to an “extra” that a health care provider supports to meet some broad requirement for “community benefit.” (An important for instance: these services rarely get incorporated into electronic medical records.)

- We need to recognize that the boundary between “individual behavior” and “social determinants of health” is fuzzy. People might eat badly because better food is more expensive, smoke because neighborhood conditions make them anxious, and so forth. Some of this goes deeper. We have known for year that adverse childhood experiences influence people’s life-choices their entire life. And newer research is showing that group identities, whether the group is optimistic or pessimistic, influence outcomes. Similarly, that the experience of particular social networks influences individual actions. (For instance, people in a community where smoking is more prevalent are more likely to be smokers, even when other factors are held constant.) These are not reasons for ignoring the consequences of individual behaviors. But they must be recognized if we are really going to change them.

All of these suggest that, as clearly important as “individual behaviors” are in influencing health outcomes, we are going to a need a different approach to addressing them than is currently the case. We need to figure out what is the right approach and not let the Republican inappropriate use of “individual behavior” cause us to lose sight of what needs to be done here.

Making health care a right, while sensible and the morally right thing to do, seems like an impossible dream given the Republicans’ hard-heartedness and lack of compassion for the poor and working class.

LikeLike

Agreed, healthcare should be considered a right, but would that be enough to protect it? Public education has long been considered a right in this country, and look how it’s been invaded and distorted by commercial forces. All sectors have been bulldozed by “market forces” since the 1980s “Reagan Revolution.” How to get market forces back in the business sector where they belong? And why not make the healthcare field and the education field open only to non-profit entities? They can pay good salaries for innovation and good service — without the pressure to earn a fat level of profit on top of it all.

LikeLike

I agree that is part of the problem. But it is tantamount to saying that part of America’s problem is that it is America. Absolutely true. But I suspect this is a bridge much too far.

LikeLike

Healthcare as a right is noble and, unfortunately, branded as a liberal notion. I’ve been mulling over a more conservative approach. Government is most important in providing necessary services that can only be provided collectively. We cannot build our own roads, protect our own borders, individually police our communities, regulate markets…. The list goes on. It appears clear that except for the wealthy, the list now includes providing our own health care with any sense of security. Payment for treatment of a serious disease or even of a serious injury is now, I suspect, well beyond more than half the American public. And between medical inflation and growing income inequality, that portion is growing. A collective approach is the only practical solution. This is true not only for providing health security to the majority of Americans, but also for controlling costs of medical care — something the free market is quite clearly not designed to do. I hold both for the notion of healthcare as a right, and for the reality that it is broadly available only when tackled collectively. The political advantage of the latter approach is that it focuses on the needs of the majority, whereas the former is perceived (with growing untenability) as focusing on the indigent.

LikeLike